As detailed in Mike Tuchscherer’s Reactive Training Manual, traditional percentage based programming is highly flawed. The crux of the issue is that most programmers make two fatal assumptions: 1) they assume a lifter’s one rep max is fairly stable from training session to training session and 2) they assume by knowing how much work a lifter has done, that they know what effect the training session has had on them. Both assumptions are false due both to individual differences and the phenomenon of “readiness”.

If you’d rather watch than read:

Readiness in Powerlifting

First, let’s address readiness. We call your ability to perform on any given day your level of “readiness”.

If you’ve been lifting for more than a few months, you’ve undoubtedly experienced what we’ve all come to know as “good days” and “bad days”. For whatever inexplicable reason, you are sometimes capable of lifting much heavier weights than you otherwise normally can. On other days, the exact opposite is true and you cannot match even your average performances. Now, this may be due to outside life stress such as a break-up, moving, getting in a fight, or even something more trivial, but what truly matters is that “life happens”.

Listen to Your Body

This is why lifters who have been in the iron game for ten years will talk to you about the importance of listening to your body. These guys have internalized all of these concepts without giving them names such as autoregulation, readiness, or fatigue management. However, just because you’re a younger or a newer lifter, doesn’t mean you have to wait ten years until you can start to learn to listen to your body. That’s the whole point of autoregulation. Instead of “listening to your body”, you simply react to your performance in the gym. Anybody can learn autoregulation and you can begin implementing it relatively quickly instead of having to wait for ten years.

Readiness and Intensity

When “life happens”, a program that calls for a fixed percentage of some theoretical one rep max that you did that one time in the past might have you working much lighter or heavier than intended. For example, if a program calls for “85%” that typically results in about five reps. On good days however 85% might be 7-8 reps. On bad days, 85% might only be 2-3 reps. 85% isn’t 85%. It depends on your readiness which constantly fluctuates. With fixed prescriptions we can’t be sure that we are actually doing 85% for that particular day’s level of readiness.

Your Volume Is Not My Volume

Perhaps the biggest mishap of traditional programming is the assumption that if you can prescribe the volume, you can prescribe the training effect. This couldn’t be less true and it is due both to readiness and individual differences.

In terms of individual differences, the problem becomes rather obvious. Say we have two trainees: a 55 year old master’s lifter on a calorically restricted diet and an 18 year old novice lifter currently gaining 1-2lbs a week. Their nutrition, age, and training advancement are completely different. Are we really going to be so foolish to assume that a “5×5” workout is going to have the same effect on these two lifters? For the older lifter, a true, difficult 5×5 may cripple them for an entire week. For our growing novice, this might be just enough volume to push him forwards for his next workout two days later.

Fatigue Matters

We have to differentiate between fatigue and volume. Fatigue is the amount of stress we’ve accumulated from a workout. Volume is the amount of work we actually did in the workout.

Now, of course, these things are highly correlated, but they’re not synonymous. The higher the level of volume tolerance an individual possesses, the less fatigue a given amount of volume is going to cause. Because “fatigue” is the far better proxy for the size of the dose of stress we’ve given the body, we’re more interested in how much fatigue a workout has caused rather than how much volume it contains. We need to begin to think of volume as the tool that we use to create fatigue rather than thinking of it as what literally drives progress.

Readiness is also largely important when it comes to fatigue considerations. That is, even for the exact same individual, different levels of volume will cause different levels of fatigue on certain days. Let’s say that, hypothetically, you only got two hours of sleep last night, had to fight traffic for two hours on the way home from work, and you find that your dog is sick and throwing up when you finally do get home. Do you think that you’re going to be able to handle the same amount of volume as usual? Even if you can, do you think it will cause the same amount of fatigue? Of course not.

Because of these problems, preplanned, prewritten programming based on percentages is highly flawed. What we truly need is a way to regulate our weights and volume on any given training session to ensure they match our particular level of readiness that day. Let’s take a look at how we can do that.

Explaining RPE

While RPE was first mentioned in a lifting context in Supertraining, it was really Mike Tuchscherer’s Reactive Training Systems that first popularized the concept amongst powerlifters. RPE stands for rate of perceived exertion. RPE is a subjective indicator that gives us a way to communicate the difficulty of a set.

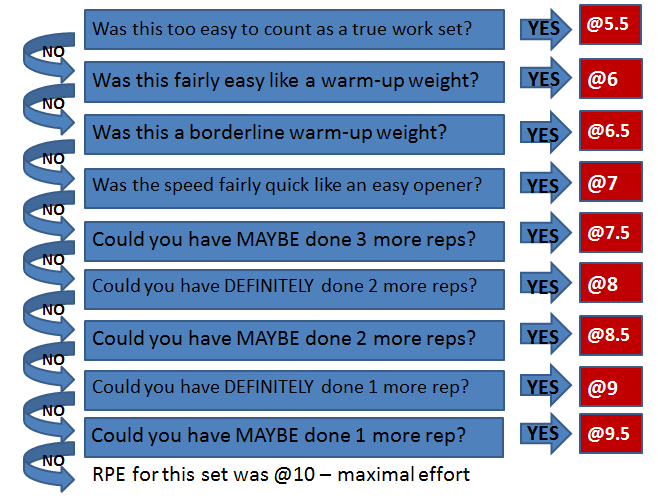

Here is the current Reactive Training Systems RPE Chart:

RPE Scale:

Why does RPE Matter?

What is the significance of RPE you ask? RPE allows us to ensure that we are working in the proper intensity zone during any given workout. Rather than prescribe someone a fixed percentage, that may or may not correlate to their readiness that day, we can prescribe reps and RPE.

Just for example, we know that a five rep max is about 85%. Instead of telling the lifter to do 85% of their theoretical one rep max, we just tell them to “work up” to x5@10. Depending on their readiness that day, the weight is going to be different. This is autoregulation; your weight selection is determined by how you’re doing on THAT particular day. Instead of you fitting to the program, the program fits to you.

The RPE Chart

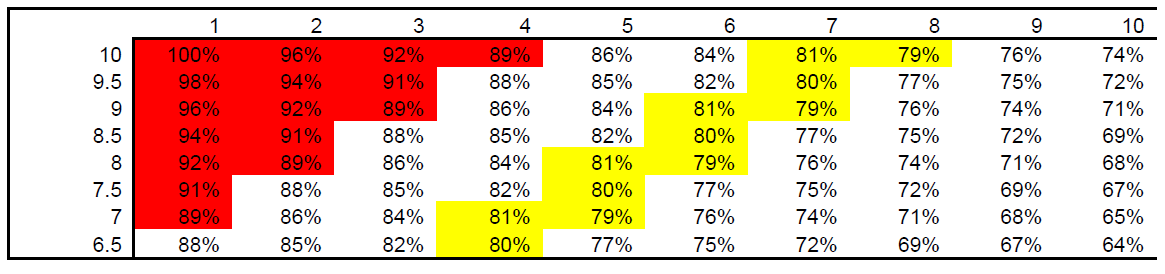

We can use the following chart to get an idea of what any particular rep/RPE combo will give us in terms of intensity:

For example, a triple at RPE 9 would equate to approximately 89%. A set of 5 at RPE 8 would equate to approximately 81%. You get the picture. Just match the reps and RPE to the percentage on the chart.

With a firm grasp of RPE, you can see that we no longer need fixed percentage prescriptions anyways. With RPE, we can always work in the exact intensity range that we were intending. Instead of our weights being based on some theoretical max that might have happened three or four months ago, our weight selection is completely autoregulated by our performance during each workout. On good days, you’ll take advantage and smash PRs. On bad days, you’ll also take advantage by avoiding going too heavy, missing lifts, and just digging yourself into a recovery deficit.

Fatigue Percents

As you’ll recall, the second issue was that of fixed volume prescriptions. We don’t necessarily care about how much total volume our trainees are doing. We care what effect that volume is having. In other words, we need a way to measure fatigue versus simply measuring volume.

Using RPEs, we can now do that through a concept called “fatigue percents”. For example, let’s say our workout prescription calls for x5@9 (five reps with one rep left in the tank). Instead of telling a lifter to do five sets at x5@8-9 or something like that, we can prescribe them “5% fatigue” instead.

Here is how it works:

1) The lifter works up to their initial top set. Let’s say 500×5@9

2) The lifter then subtracts 5% from this number to get 475.

3) The lifter will repeat sets at 475 until he hits an RPE 9. This may take one set or it may take ten sets.

4) Once an RPE 9 is reached at 475, we know that “5% fatigue” has occurred because he is now doing 5% less weight with the exact same difficulty as he did 500. In simple terms, his lifting ability has dropped 5%.

Boom! We now have a way to measure fatigue instead of volume.

Theoretical Example:

455×5@7

480×5@8

500×5@9, this is the “initial”

475×5@8, 5% weight subtracted

475×5@8.5

475×5@9, 5% fatigue reached – workout over / move to next exercise

Fatigue Management

This autoregulation of volume is critical for so many reasons. As we’ve already mentioned, it doesn’t necessarily matter how much volume you do, it matters what effect the volume is having. By managing fatigue, instead of volume, the volume is autoregulated until it has the precise effect we want it to have. For older lifters, it will take less volume to reach the same amount of fatigue. For lifters having a great day, it will take more volume than usual. Regardless, the volume for that session is completely optimized to the lifter.

Using Fatigue Percents

There are a few important guidelines in terms of using fatigue percents in the real world: 1) understanding the effect of different percentage ranges and 2) time limits.

Understand that the following information represents guidelines taken from The RTS Manual. I have added additional notations and explanations to clarify the concepts.

These fatigue % ranges are determined entirely from Tuchscherer’s practical experience coaching hundreds of athletes. Nonetheless, practical experience is always subject to error. Keep that in mind. These percentages may not work out exactly for you. Take personal notes, pay attention, and adjust over time.

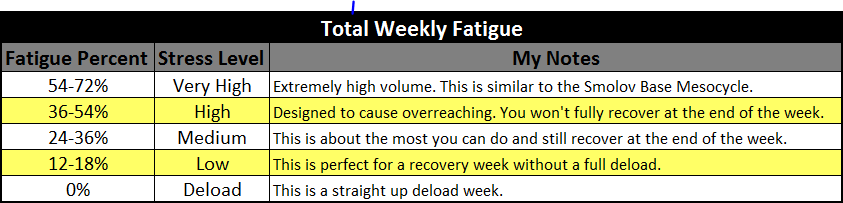

Total Weekly Fatigue and Stress

Exercise Fatigue and Stress

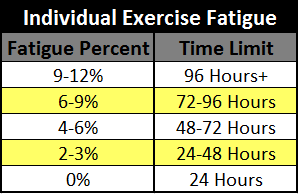

The following assumes three exercises per workout. We’re talking specifically about individual exercise fatigue here.

Fatigue Percents and Time Limits

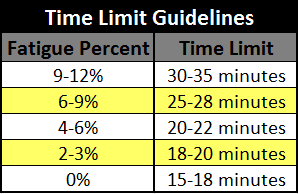

As far as time limits go, obviously, you’re going to be able to do more back-off sets if you rest fifteen minutes between sets. That isn’t the point here. We need to keep the workouts to a reasonable length because: a) we’re not professional athletes, b) this allows us to add more volume over time without running into scheduling issues, and c) most importantly, a time limit gives us a way to standardize each session; when conditions are vastly different in terms of time limits, fatigue %s lose some of their value because you can’t compare 5% fatigue accumulated on 3-5 minute rests to 5% fatigue accumulated on 15-20 minute rests. You need to compare apples to apples.

Time Limit Guidelines

The time limit begins as soon as you start your first warm-up with weights on the bar.

For Each Exercise:

Fatigue Percents and Load Drops

While Tuchscherer discusses many different means and methods of using fatigue percents in the RTS Manual, I’m going to familiarize you with only two of them because they are the most common.

The first method is called the “load drop”. We’ve already discussed this method without naming it. With the load drop method, you simply work up to an initial set, take off the prescribed % (drop the load), and then perform back-off sets with the lowered weight until you hit the same RPE as the initial set.

Here’s another example:

90×3@7

95×3@8

100×3@9, 10% load drop

90×3@7

90×3@7.5

90×3@8

90×3@8.5

90×3@9, 10% fatigue reached

Fatigue Percents and Repeats

Repeats are somewhat similar to load drops excepting that we don’t work up to our highest RPE initially. Instead, we find a lower initial weight and repeat that weight until it becomes a higher RPE. This generally results in more overall volume being done at a much lower intensity. This makes it great for when you’re specifically shooting for a high volume workout.

For example:

90×3@7

95×3@8

95×3@8

95×3@8.5

95×3@8.5

95×3@9, 3% fatigue reached

To calculate how much fatigue you’re accumulating from repeat sets, you have to consult the RPE Percentage Chart.

In this case, the difference between x3@8 and x3@9 is 3% fatigue.

Picking Weights with Autoregulation

Another issue I want to address here is how you can actually structure progress into your workouts with RPEs. With more traditional percentage based programs or even linear programs, you know when it is time to go for a PR because the programs tell you it is time. You load up the weight and you either get it or you don’t.

With RPEs, there is a large grey area. Should you try for a PR every single workout and just adjust based on the RPEs? Should you always plan under your PR and just increase the weights when you feel good? Both of those approaches are viable, but they’re a little extreme.

The best way to aim for progress on an autoregulated program is through estimated one rep maxes (e1RM). Your e1RM is calculated using the RPE Percentage Chart (see above). If you did 405×3@9, we look up x3@9 in the RPE Chart and see that it is 89%. We then divide 405 by .89 and we’d get about 455.

For your next workout, you’d simply want to shoot for something like a 2-3lbs/1kg PR. Let’s say your next workout required x5@9. We’d go to the RPE Chart and see that this is equal to about 84%. So, all we have to do is take 455 and multiply it by .84. We’ll get ~382. Instead of doing 382, we’ll plan on doing 385. We know now that if we can get 385×5@9, we’ve set a ~3lbs PR on our e1RM. As long as our e1RM is trending upwards over the weeks and months, we know we’re making progress.

Knowing a “Good Day” from a “Bad Day”

This is all fine and dandy, but I am sure many of you are wondering how to put these concepts into practical use. Sure, you can calculate what you need for a PR, but how should you adjust if you’re having a good day or even a bad day? That’s a great question and here is the standard recommendation that I’d make.

Instead of trying to jump straight to your top set, use “work-up” sets. I’d recommend doing a set at 90% of your e1RM goal, another set at 95%, and then finally your top set at 100%. Because each set is spaced about 5% apart, we can use these sets to estimate whether it is a good day or a bad day.

For example, let’s say we needed to work up to 500×5@9 for our small PR. Our work up sets would work out to something like the following:

450×5@7 (90%)

475×5@8 (95%)

500×5@9 (100%)

Now, if we were capable of 500×5@9, using the RPE Chart, we’d expect 450×5 to be about an RPE 7 and we’d expect 475×5 to be about an RPE 8. If during your warm-ups, 450×5 is an RPE 6 or 475×5 is an RPE 7, you know you’re probably going to have a great day. If you do 500×5 and it is an RPE 8, well, you know can do another set with a higher weight! If you get within 0.5 RPE, I’d just call it there rather than doing another set.

Obviously, the reverse is also true. If you do 450×5 and you get an RPE 8, well, you might need to lower your expectations for that day. 475 might end up being your top set. That’s okay. Bad days happen too. That is the whole point of autoregulation.

Conversely, say you’re just having a day that is going as you’d expect, it sets you up to for a small PR on your top set. In this manner, you make consistent, small progress on most of your training days.

Final Thoughts

Well there you have it! Hopefully that clarifies a lot of the questions surrounding how to actually use autoregulation in training.

If this style of programming is intriguing to you, I highly encourage you to check out Mike Tuchscherer’s website for more information. Though Mike’s RTS Manual is slightly out of date with how he currently programs, if you’d like further information on how to use autoregulation to design your own personalized programs, you should grab a copy of the manual. Frankly, whether you get the information from me, Mike’s website, or the RTS Manual, if you consider yourself a student of the iron game, you MUST familiarize yourself with these concepts.

This is the future of powerlifting training and probably weight training programming in general. It just hasn’t caught on yet. ANY program can be modified to use autoregulation instead of percentages. In fact, creating custom programs using autoregulation is one of my specialities. If you’d like more information on custom coaching and custom programs using autoregulation, shoot me an email:

I know this can be a complicated subject to master. If you have questions, please ask!

Like this Article? Subscribe to our Newsletter!

If you liked this articled, and you want instant updates whenever we put out new content, including exclusive subscriber articles and videos, sign up to our Newsletter!

Questions? Comments?

For all business and personal coaching services related inqueries, please contact me:

Very interesting stuff. A lot of guys touch on this in their blogs/writing but never to this level of specificity. Can’t wait to see the intermediate program.

How are the fatigue percentages determined for individual exercises? For example if I did a 5rm rpe of 10 on Monday I would not be able to do that again in 24hrs. Assuming that 0% fatigue means no load drops or repeats

Yeah, this is one of the limits of fatigue. You have to keep in mind that total stress is influenced by both intensity and volume. Then again, if ALL you did was a 5RM, and no other volume, that wouldn’t be incredibly difficult to recover from. Consider something like the Bulgarian Method that often has people maxing out every day.