In the inaugural edition of the PowerliftingToWin Nutrition Series, we established that nutrition in Powerlifting serves primarily two purposes: 1) weight management and 2) performance enhancement. In the service of these goals, the conclusion was drawn that, with our eating habits, we should aim to a) gain as much muscle as possible, b) maintain a competitive body fat percentage, and c) spend as much of our training time in a caloric surplus as is possible.

In other words, we’ve established the “what” of powerlifting nutrition. In this article, we’re going to describe the “how” from a broad perspective. I’m going to outline the general nutrition strategy employed here at PowerliftingToWin. In subsequent articles, we will fill in the gaps and provide the exact details of execution that make the plan practical and applicable in the real world.

If you’d rather not have to wade through all of these articles, and you’d like to get straight to the point, our eBook EatingToWin delivers all of this information in a format that allows you to quickly navigate to the sections you care about most.

If you’d rather watch than read:

Protein Ratio

Before I can delve too much into nutrition strategy, we need to discuss a phenomenon called “protein ratio” or “p-ratio”. P-Ratio is the proportion of weight an individual will gain as muscle when overfeeding and the proportion of weight an individual will lose as muscle when losing weight. That’s right; whenever you lose weight a portion will be “lean body mass” and whenever you gain weight a portion will be fat. If you want more scientific details on the subject, check out Lyle McDonald’s book on the topic.

There is good news and bad news. First, here is the bad news. P-Ratio is primarily genetic. Some individuals are simply better at accumulating muscle when overfeeding (bulking) and some individuals are better at keeping muscle when underfeeding (cutting). Some blessed souls are quite good at both. Of course, the opposite set of genetics exists as well. Most people though tend to gain mostly fat when overfeeding and lose mostly fat when underfeeding.

Now, here is the good news. P-Ratio can be influenced in three primary ways: training, nutrition, and “supplementation”. We’re not going to discuss drugs here, but suffice it to say that performance enhancers work and that is why athletes take them. In terms of training, well, at this point I’m just going to assume you have your programming in check. If you’re unsure, review the PowerliftingToWin Programming Series.

Of course, our focus in the rest of this article is going to be on the nutrition aspect of P-Ratio. Why? Well, let’s remind ourselves of our goals: we need to remain at a competitive body fat percentage, we want to gain as much muscle as possible, and we want to spend as long as we can in a caloric surplus. That means we want to gain mostly muscle whenever we bulk so that we can extend the bulking period as long as possible. The more muscle we can accumulate, as a proportion to each pound gained, the longer it will take to reach the limits of “competitive body fat”. Likewise, when we diet, we want to do so quickly and efficiently (without losing muscle) so that we may return to overfeeding as soon as possible.

Competitive Body Fat Percentage: How Fat is too Fat?

Before we can go any further into the strategy, we need to define what a “competitive body fat percentage” is. Without this definition firmly in place, we have no idea when we should be bulking and when we should be cutting.

It is important to note that my recommendations here are made for males. If you’re a female, please add 6-8% to all values.

Let’s start with the upper limits of competitive body fat. In my opinion, a lifter with competitive interests should not exceed 15% body fat. There are three reasons for this seemingly arbitrary distinction.

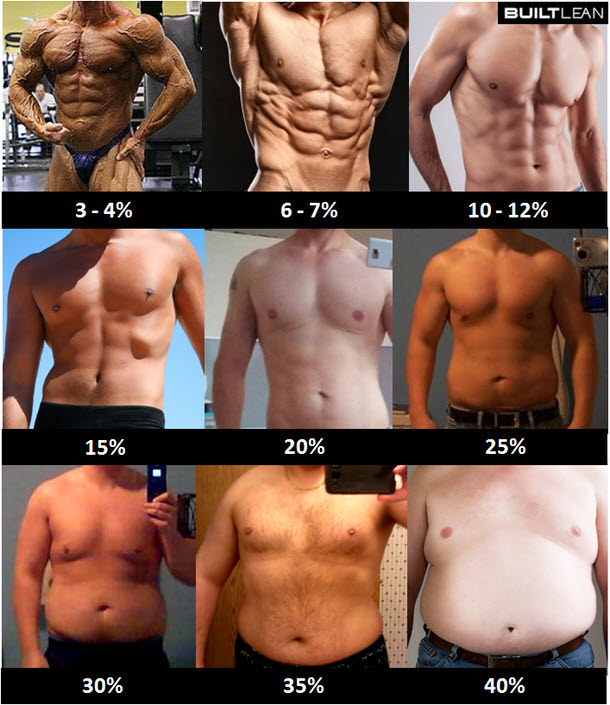

The more muscle you have, the bigger the visual difference between two given percentages.

Photo: www.builtlean.com

The first reason is that this is approximately the level where P-Ratio begins to worsen. In an incredible oversimplification of hormonal milieu, this is due to the fact that the fatter you are, the more estrogenic you become. Fat cells act as receptors for estrogen which binds testosterone. With less free testosterone in your system, the quality of your gains begins to diminish. This is not only a health issue, this is not only a quality of life issue, this is not only an aesthetics issue, but it is also a performance issue. So, even if you don’t care about life outside the weight room, it is still in your best interest to avoid becoming too fat.

The second reason, and perhaps most important, is that this also tends to be the area where leaner competitors will just start to wipe the floor with you in the same weight class. If you are sitting at 15%+ and your top competitors are around 10% body fat, they might have an insurmountable advantage in terms of muscle mass.

The third reason is that we need to be within striking distance of leanness at any given time. At 15%, you’re never more two or three months of dieting away from being completely shredded if necessary. This is plenty of time to get ready for an important meet. At 20%, you may need four of five months of dieting which is usually more time than most powerlifters have between their meets.

The one exception is a lifter who is 6’3”+ and wants to compete as a super heavyweight. For those who are unfamiliar, the super heavyweight class has no weight limits. The taller you are, the more of an advantage you’re at. Unlike any other weight class, you can weigh as much as you want. So, a guy who is 6’8” and can reasonably weigh 400lbs is going to beat a 6’3” individual who only weighs 300lbs.

For more information on picking your weight class, check out our article on the subject.

Competitive Body Fat Percentage: How Lean is too Lean?

Believe it or not, this principle applies on the leanness end of the spectrum as well. Depending on your genetics, you’re going to want to avoid going any lower than 8-10% body fat. Let me explain.

At levels of extreme leanness, your body engages various mechanisms designed to protect you from starvation and death. This is going to include increased metabolic efficiency (slowed metabolism) and the shutting down of various hormonal processes that are considered superfluous in times of starvation.

In simple terms, you’re not going to be able to eat very much without gaining weight. This is detrimental because a performance athlete, in the vast majority of cases, should be eating a diet rich in carbohydrates. If your metabolic rate drops so low that you can only fit in 100-200 carbs per day, you’re simply not going to perform as well or recover as well due to the severely diminished amounts of energy substrate within your system.

Likewise, extreme leanness tends to depress testosterone and hormones with important implications for training. Again, your body is trying to stay alive; it thinks you’re starving. This is not a hormonal environment that is optimal for peak performance.

The difficulty is that people will start experiencing these symptoms at different levels of body fat depending on their age, genetics, level of musculature, dietary intake, and a myriad of other factors. Those of you who tend to be naturally lean will probably be the ones who can handle getting down to 8% without serious performance detriment. Most people will find that 10% is about the lowest they can go. Others still, usually those who are naturally bigger and fatter, will have difficulty dropping below 12%.

It is what it is. There is no sense in complaining. There are advantages and disadvantages to all types of genetics. You’ll have to find what works for you through actual trial and error. You just can’t know your limitations until you’ve done a few diets.

PowerliftingToWin Nutrition Strategy

In light of what we’ve discussed thus far, borrowing from a concept originally developed by Lyle McDonald, I’d make to you the following recommendations:

- If you’re at or above 15% body fat, slow cut down to 8-10% body fat.

- If you’re below 15% body fat, slow bulk up to 15% body fat.

- Squeeze into the lightest weight class you can through water cutting.

It is really that simple.

Now, while I’m going to save the specifics of dieting and water cutting for future articles, I do think I need to define “slow cutting” and “slow bulking”.

”Slow” Bulking

For our purposes here, slow bulking is going to be defined as gaining weight at a rate that is appropriate for your level of training advancement. This is incredibly important because if you attempt to gain weight too quickly, you’re guaranteed to gain an unnecessary amount of fat. Your P-Ratio will become less favorable.

I tend to break slow bulking down into roughly three categories of trainee:

-

- True Novice

A true beginner is someone with NO EXPERIENCE whatsoever. This person should gain 1-2lbs (0.5kg/1kg) per week for a period of 1-2 months during their linear progression. It is time to stop gaining at this rate when one can no longer sustain 10lbs/5kg jumps on squats/deadlifts and 5lbs/2.5kg jumps on bench/press every single session.

-

- “Advanced” Novice

The “advanced” novice is someone who is still capable of linear progression, but they are no longer making light speed progress with large jumps. Once you have to start using 5lbs/2.5kg jumps on the squat/deadlift and 2.5lbs/1kg jumps on the bench/press, you’re probably at this level. This period can last anywhere from 3-6 months or so. During this phase, you’re going to want to shoot for a weight gain rate of approximately 0.5lbs-1lbs/0.25kg-0.5kg per week.

-

- Everyone Else

While it is true that someone who has been training for five years gains much more slowly than someone who has been training for just one year, I don’t find it incredibly productive to gain weight at a rate too much slower than 0.5lbs/0.25kg per week. Aim any lower and you’re more likely to just spin your wheels and maintain weight due to fluctuations in calories burned throughout the week. Aim any higher and you’re guaranteeing yourself a poor P-Ratio because you’re simply not capable of synthesizing muscle tissue at a super-fast rate anymore. Past the novice stage, you can’t expect too much more than a pound of muscle per month during the best of times. I’d aim to gain no more than 0.5lbs/0.25kg per week during the rest of your career when bulking. I’d prefer if you gain less than that and have to stretch the bulk longer rather than you gaining faster, getting fat quickly, and having to cut again very soon.

In many ways, past your first year or two, you should emphasize slowly increasing your intake over time above and beyond whether or not you’re actually gaining weight. Push your intake as high as possible. As long as your weight is maintaining or moving up by 0.5lbs or less per week, and you’ve increased your intake from the previous week, that is a successful week in your bulk.

”Slow” Cutting

My version of slow cutting really isn’t slow at all: I’d advise you to lose between 0.6-0.8% of your body weight per week. For most average sized males, this works out to about 1-1.5lbs per week or so. Obviously, this is going to be proportionate to your current body weight.

The reason that I prefer to keep the cuts “slow”, at least relative to, say, Lyle McDonald’s Rapid Fatloss Diet, is that this allows us to keep food intake as absolutely high as possible while we diet. The higher intake is, the more energy substrate we keep in our system, the better we perform, and the better we recover. This is a huge deal. Maintaining performance during dieting is one of the key factors that determines how much muscle you keep.

Additionally, when you diet “too fast”, you influence P-Ratio negatively. The faster you diet, the more likely you are to lose muscle during the process. By keeping intake as high as possible, and by dieting at a reasonable rate, we can minimize the risk of losing muscle and strength.

Even still, ~0.7% of body weight lost per week is much faster than our bulking rate and we’ll still be spending much of the year in a caloric surplus.

Final Thoughts

One more time, here is the revised EatingToWin Nutrition Strategy in a nutshell:

- If you’re at or above 15% body fat, slow cut down to 8-10% body fat.

- If you’re below 15% body fat, slow bulk up to 15% body fat.

- Squeeze into the lightest weight class you can through water cutting.

Slow Bulking: Gain up to 0.5lbs/0.25kg per week

Slow Cutting: Lose 0.6-0.8% of your bodyweight per week

In the next installment of the PowerliftingToWin Nutrition Series, we’re going to discuss how to actually measure your body fat. It is all well and good to know these percentages as general references, but if you don’t know how to measure your body, it sort of defeats the purpose, doesn’t it?

Did you enjoy the Powerlifting Nutrition Series?

If so, I highly recommend you check out our eBook: EatingToWin. The book contains absolutely everything you need to know about how to set up the optimal diet for YOU personally as a powerlifter, how to identify the right weight class to maximize your competitiveness, how to cut weight like a PRO so that you can drop a weight class without performance loss, and, of course, an entire section on recommended supplements with the supporting evidence behind each recommend. Grab your copy now!

Like this Article? Subscribe to our Newsletter!

If you liked this articled, and you want instant updates whenever we put out new content, including exclusive subscriber articles and videos, sign up to our Newsletter!

Questions? Comments?

For all business and personal coaching services related inqueries, please contact me:

Table of Contents

Powerlifting Nutrition: How To Pick Your Weight Class

Powerlifting Diet: Cutting and Bulking

The Best Way To Measure Body Fat For Powerlifting

When To Move Up A Weight Class

How To Cut Weight For Powerlifting: 24 Hour and 2 Hour Weigh Ins

How To Diet For Powerlifting: Calories, Reverse Dieting, and More

Setting Up Your Powerlifting Macros

Meal Frequency and Nutrient Timing in Powerlifting

Eating Healthy for Powerlifting

Best Powerlifting Supplements