In the last installment of the Nutrition Series, I discussed how to optimally cut and bulk for powerlifting. One of the main tenets of the strategy I advocated was that one should bulk up until about 15% body fat or so, then cut down to 8-10% body fat, and simply repeat the process over time in order to accumulate muscle mass (add 6-8% body fat to these numbers if female).

This is all well and good but it does invite one very important question: how exactly do I measure my body fat percentage?

If you’d rather watch than read:

Body Fat Measurements

Now, many of you may not know this, but there is only one way to truly, accurately get a body fat percentage – dissection! Raise your hand if you’re willing to die for your body fat percentage. No takers? What a shocker.

Measuring body fat is a huge deal in high level research science. This information is needed for all sorts of studies involving body composition in fields such as pharmacology, cardiology, nutrition, and too many others to list. As you might imagine, a number of methods to estimate body fat have come into existence over the years. This is nice because we can now avoid killing all our subjects to get our body fat measurements.

Every single one of these devices and methods is subject to error. People constantly champion DEXA as the gold standard, and DEXA is extremely accurate both across a population and compared to other measures, but even DEXA contains a significant margin of error for specific individuals because it uses body density to estimate body fat. On some occasions, individuals will show substantially different densities in their bones, minerals, etc. For some individuals, not populations mind you, this margin of error can be as high as 5%. 5% in either direction is literally larger than the entire suggested range I gave above of 8-15%.

Body Fat Measurement: Accuracy vs. Consistency

Look, I am not about to tell you that measuring body fat is pointless and worthless. However, hopefully it is clear that accuracy is not our main goal when it comes to tracking body fat. If for no other reason this is the case simply because accuracy is not possible.

Our primary goal is actually consistency. That is, we want to use a tool that is going to provide consistent results over time in order that we may confidently track changes. We can then establish “anchors” to reality via both our measurements and our performance in the gym to help us determine our “functional body fat range”.

Functional Body Fat Range

Look, as performance athletes, our specific body fat percentage is completely irrelevant. What matters here is performance. The real question is “how lean can I get without hurting my performance”? Again, the specific percentage does not matter. Who cares if it is 8.35% or 11.42%? It does not matter.

Remember, we want to squeeze into the lightest weight class possible while still maximizing muscle mass and performance on the platform. At some point, getting any leaner starts to cost us significant muscle mass and the accompanying reduced caloric intake will lead to reduced performance as well. This point represents the minimum end of our “functional body fat range”.

As such, the most important thing we can do is determine when that performance drop starts to occur. This isn’t particularly difficult as it pretty obvious to any lifter when his performance is clearly trending down over a handful of week (NOT small fluctuations). The more interesting part is keeping track of a set of measurements that we can then correlate to this performance drop. By doing so, in the future, we know to avoid letting ourselves reach such measurements.

Recommended Body Fat Measuring Tools

For the aforementioned purpose of determining functional body fat range, I have four suggested tools: a mirror/camera, a tape measure, a food log and a scale, and a consistent measurement method.

-

- The Mirror and/or Camera

The mirror and the camera provide us with subjective “visual” data. That is, we can estimate what our body fat is simply by looking at ourselves. Now, this obviously isn’t going to be accurate, but the reality is that we don’t need accuracy, we need consistency. You want to note how lean you look when performance starts to drop. Take a mental snapshot or, better yet, take weekly pictures for your records.

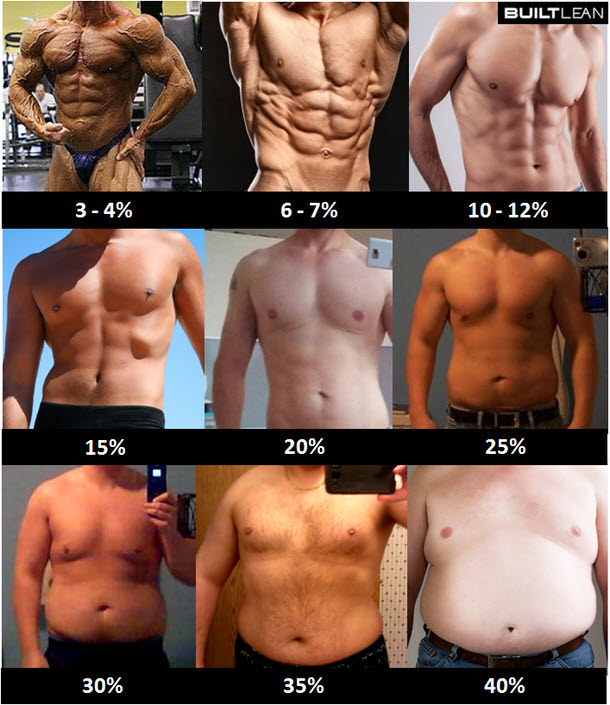

You can compare your current composition to the following picture to give yourself a “visual reference range”.

The more muscle you have, the bigger the visual difference between two given percentages.

Photo: www.builtlean.com

If you look like you’re clearly above 15%, even if other measurement systems say otherwise, assuming you don’t have self-image issues, it is probably time to cut.

-

- Tape Measure

I also suggest using a tape measure to record the circumference of your waist directly around the umbilicus (belly button). This gives us an objective piece of data to work with as well. Waist measurement is generally a great confirmation of what is happening with body fat (female should track hip measurement as well). Waist changes correlate extremely well with changes in body fat percentage. As such, we can note what our waist measurement is when we are at the tail end of our functional body fat range and, in combination with the mirror, we can use this information to help make decisions about when to end our cuts and bulks.

In general, I would allow for no more than a 3” gain on your waist from your minimum functional body fat point to the end of a bulk. The reason for this is that it shouldn’t take you more than ~3 months to diet off a 3” gain on your waist. Unless the mirror is saying something drastically different, your waist measurement is a good objective piece of data to help check yourself and prevent you from getting too carried away with your bulking phases.

Personally, I am a fan of the Navy Method for estimating body fat. Again, accuracy isn’t our goal here, but rather consistency. The Navy Method simply requires taking the circumference of your waist and neck in combination with your height to produce a body fat estimate. This can provide you a decent hard number to compare to the mirror and other means. If you have an unusually large or small neck, this won’t work well for you, but, for many others, it will produce a useful number. Always remember it is just an estimate. Don’t fall into the trap of giving the specific number too much credit. Use your other measurement methods as checks and balances.

One issue with tape measures is that you can pull them to different tightnesses. I’d recommend grabbing a MyoTape to prevent this issue. A MyoTape is a tape measure that simply clicks once you’ve reached a certain level of tightness. This allows you to get the same amount of tension every time. I think it is worth the investment.

- Food Journaling and Scale Weight

The third tool that I would suggest using is the combination of scale weight and a food log (MyFitnessPal.com is free and easily the best food logging resource). Tracking your macronutrient intake is essential to optimizing powerlifting nutrition in the first place, but we can also use trends in intake to estimate when we are running up on the limits of our functional body fat range. When intake begins to drop very low to produce further weight loss, you know you aren’t too far away from reaching that point.

For most males of average size and greater, say 75kg/165lbs+, you’re flirting with muscle loss when you spend any prolonged period of time below an average intake of ~2000kcal or so. However, don’t use that as a hard and fast rule. Compare your intake numbers to your performance in the gym. Make a note of what intake levels seem to correlate with reduced performance. This is yet another metric to track in terms of when you need to think about upping the calories again.

- Consistent Measurement Protocol

While a consistent measurement protocol isn’t exactly a tool, it is of imperative importance in this entire process. If you are not taking your measurements under relatively similar conditions, they’re meaningless. Scale weight can fluctuate 5-10lbs a day in larger individuals. Waist measurements can fluctuate by inches after a meal. You’ll even get varying levels of bloat throughout the day which influences how you look in a picture or a mirror.

My recommendation is that you ALWAYS perform your measurements under the exact same conditions. The best way to do this is to do any measurements first thing in the morning after using the bathroom. Pictures should be taken anywhere from once a week to a once a month and they should always be taken using the same camera, lighting, and general set-up. Waist measurements can be taken weekly first thing in the morning. For scale weight, the most accurate method of tracking is to take a running weekly average of your weight. This means that you weigh-in every single day. You’ll record each value and track them in a spreadsheet. This way, you eliminate some of the day to day variance when comparing across weeks. Once and twice weekly weigh-ins are also viable; they’re just less accurate.

Cutting and Bulking Decision Protocol

Alright, let’s bring all of this information together into a coherent protocol that can actually help us make decisions.

Remember, we are not concerned with ultimate accuracy; we want to establish a set of reference points that allow us to make practical decisions in the real world.

Every week, first thing in the morning after using the restroom, you will do the following:

- Weigh-in and record your weight

- Measure your waist around the belly button; measure your neck just under the Adam’s apple; use this data to calculate a body fat estimate using the Navy Method

- Take a picture with the same camera, same lighting, and same general set-up

Use the above data to make the following determinations:

If Cutting:

Is performance in the gym significantly down in the last two weeks or so?

-

- No.

Keep cutting.

-

- Yes.

Note your Navy Body Fat estimate, visual leanness, and intake. Use these data as reference points for when consideration of when to end your next cut. If both the Navy Method and your visual leanness estimate indicate you are still well above ~12-13%, the performance problem is likely due to other issues. If you are below ~12% or so, you should start a weight gain phase.

If Bulking:

Do both the Navy Method and your visual reference guide suggest you are ~15%+?

-

- No.

Keep bulking.

-

- Yes.

If your waist has grown ~2.5-3” since your last cut, it is time to begin your next diet phase.

Moving Forward

In the next installment of the PowerliftingToWin Nutrition Series, we’re going to get into the meat and potatoes of how to actually cut and bulk through examining the scientific principles and fundamentals that underlay any performance-based diet.

Did you enjoy the Powerlifting Nutrition Series?

If so, I highly recommend you check out our eBook: EatingToWin. The book contains absolutely everything you need to know about how to set up the optimal diet for YOU personally as a powerlifter, how to identify the right weight class to maximize your competitiveness, how to cut weight like a PRO so that you can drop a weight class without performance loss, and, of course, an entire section on recommended supplements with the supporting evidence behind each recommend. Grab your copy now!

Like this Article? Subscribe to our Newsletter!

If you liked this articled, and you want instant updates whenever we put out new content, including exclusive subscriber articles and videos, sign up to our Newsletter!

Questions? Comments?

For all business and personal coaching services related inqueries, please contact me:

[contact-form-7 id=”3245″ title=”Contact form 1″]

Table of Contents

Powerlifting Nutrition: How To Pick Your Weight Class

Powerlifting Diet: Cutting and Bulking

The Best Way To Measure Body Fat For Powerlifting

When To Move Up A Weight Class

How To Cut Weight For Powerlifting: 24 Hour and 2 Hour Weigh Ins

How To Diet For Powerlifting: Calories, Reverse Dieting, and More

Setting Up Your Powerlifting Macros

Meal Frequency and Nutrient Timing in Powerlifting

Eating Healthy for Powerlifting

Best Powerlifting Supplements