The time has arrived for us to evaluate the highly popular numbered Sheiko routines. For those of you who are unfamiliar, Boris Sheiko is perhaps the foremost powerlifting coach in Russia at the time of this writing. He has worked with world champions and world record holders such as Andrey Belyaev, Kirill Sarychev, Yuri Fedorenko, Alexei Sivokon, and Maxim Podtynny.

As you might imagine, given the tremendous success of his athletes, and the uniqueness of his high volume approach, Sheiko’s programming has generated great worldwide interest. In the rest of this review, we’re going to analyze the merits and critical faults of Sheiko’s numbered powerlifting routines for powerlifters of a variety of different qualifications.

If you’d rather watch than read:

Sheiko Numbered Routines: Background, Context

Boris Sheiko possesses a formal education in sports science. His programming and methods are based directly upon the massive amount of research done by Eastern bloc scientists on Olympic weightlifters. Sheiko has been coaching for decades. Make no mistake about it, his methods proceed from both sound scientific and practical applications over many years of developing powerlifting champions.

That said, ironically, the “numbered” Sheiko routines, such as #29, #30, #31, and #32, were roughly translated from Sheiko’s book. Using online translation tools such as Google Translate and Babelfish, a handful of internet forum users went through these haphazard, awkward translations to recreate a few of his example routines in the book. The reason that the programs are called “#29” or “#30” is because those programs were, as you might have guessed, examples #29 and #30 respectively from the book.

That’s right. They are just example templates. The Sheiko templates were never created with the intent that masses of people would use them as cookie cutter templates. The Sheiko routines are not designed to be like 5/3/1 or The Cube Method; they are not cookie cutter routines! Sheiko individualizes the templates that he creates for all of his athletes.

With that in mind, we’re going to evaluate #29, #30, #31, and #32, which are all month long plans, because they were originally written together as a sixteen week peaking cycle. Though I must stress that Sheiko never intended these programs to be ran as copy/paste, cookie cutter programs, that is how most of you will end up using them. As such, we’re going to evaluate the programs from the framework of assuming they are meant to be followed to the letter rather than taken as examples.

Sheiko #29, #30, #31, #32: The Actual Program

It is literally impossible for me to display the entire program in this format. Every single one of the forty-eight workouts that compromise the program are different. What I can offer to do here is link you to the best spreadsheet that exists for the use of these numbered programs. Download the Sheiko Spreadsheet.

If you take a peak at the spreadsheet, you’ll notice that the program does have a few basic features. First of all, the numbered programs feature a thrice weekly training frequency. Generally speaking, the bench is trained on all three days, the squat is trained on Monday and Friday, and the deadlift is trained on Wednesday.

All of the sessions are quite high in volume. You perform ~200-400 lifts per week above 50%.

Sheiko Program Analysis

Let’s dig into this program a bit deeper.

The sixteen week cycle we are looking at is broken up into four blocks: #29, #30, #31, and #32. Very loosely, in terms of structure, I’d label them as follows:

#29: Prepapatory Block; Medium Volume – Medium Intensity

#30: Accumulation Block: High Volume – Medium Intensity

#31: Transmutation Block: Medium Volume – Medium-High Intensity

#32: Realization/Peaking Block: Low Volume – High Intensity

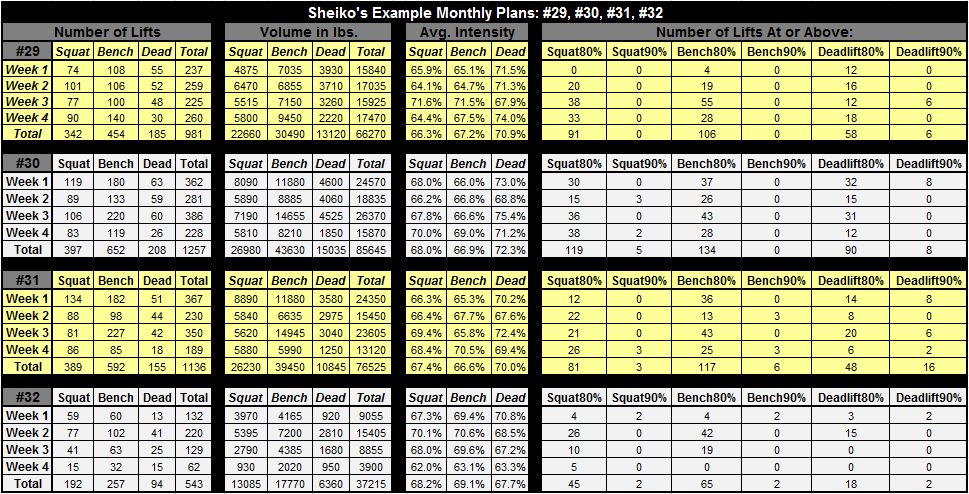

Let’s start off by explaining why #29 is a preparatory block. First of all, as you can see, the first block features relatively similar volume in all four weeks of the program. This is to simply introduce the lifter to the workloads that are typical of a Sheiko program. However, if you look closely, you’ll notice that the lifter doesn’t start performing regular work above 80% of their 1RM until Week 3 of #29. This is because the lifter is spending those first two weeks just adjusting to the shock of Sheiko’s total volume. By the end of #29, you’re primed to handle the “real” Sheiko workloads.

In #30, you’ll notice there is virtually no work above 90%. However, compared to #29, you’re doing about 50% more overall volume in Week One! To account for the fact that week one is so absolutely brutal, you’ll see that Week Two is dialed back significantly in terms of volume and lifts above 80%. However, there is no rest for the weary as Week Three hits you even harder than Week One. On #30, with Weeks 1 and 3 under your belt, Week 4 becomes somewhat of a deload as volume is again drastically reduced. This variation in volume and intensity keeps the program manageable.

Now, let’s get into #31. You’ll notice that #31 starts featuring semi-regular work above 90%. The chart doesn’t show this fact, but it also features a great deal more work above 80% than #29 and #30. The overall volume is also markedly reduced from #30. Why? #31 is designed to start leading you towards a meet peak. As such, the intensity is cranked up just a bit and the volume is commensurately reduced. This allows for recovery from the brutal #30 while preparing you for the heavy weights that are to come in #32.

#32 is a straight up peaking block. This block is pointless without first having done volume blocks before hand. As you can see, total volume and overall number of lifts performed is reduced by almost 100% from #30 and #31. That said, the work above 90% is maintained. The only real training week on #32 is Week 2. Week 2 prevents detraining during this month. However, Weeks 3 and 4 basically engage a full deload, relative to your normal Sheiko workloads because you’re expected to compete in the 4th week. Allowing the body to supercompensate from the brutal volumes done in #30 and #31 during #32 is why this block can be thought of as a “Realization” block.

Sheiko Meet Peak and Planning

Being a sixteen week cycle designed explicitly to peak a powerlifter for a powerlifting meet, #32 uses advanced compensation principles to ensure recovery during the last week of the program. In other words, the entire program is designed to maximize performance in Week 16. This is a true powerlifter’s program and a true competitor’s plan.

Sheiko Periodization

While Sheiko’s program doesn’t necessarily organize the respective blocks, #29, #30, #31, #32, into periods of focus on hypertrophy, strength, or speed, if you look closely, the program IS somewhat organized into periods of focus on the squat, bench, and deadlift.

This is an intelligent way to periodize for the late stage intermediate or advanced powerlifter. It is likely they won’t be able to aggressively pursue increases on all three lifts simultaneously because the total volume will outstrip their ability to recover. As such, Sheiko doesn’t try to improve all three lifts each week. From week to week, you’ll notice that the total volume on each lift is fairly varied.

If you look closely, you’ll notice that #29 preferentially favors deadlift volume and you actually do less benching than squatting. In #30, the squat volume and bench volume are dramatically increased by approximately 50%. The deadlift volume, on the other hand, is increased only 10% or so. In #31, this disparity is further enhanced as the squat volume reaches a level of almost twice that of the deadlift. #32, in terms of emphasis, is fairly balanced because volume is low across all three lifts as you prepare to peak for a contest.

Programming

#29, #30, #31, and #32 are roughly organized into “block” programming. As I’ve mentioned early, #29 is a preparatory block, #30 is a high volume, accumulation block, #31 raises up the intensity and lowers the volume as a transmutation block, and #32 is a pure peaking/realization block designed to lead the lifter into a contest. This is an advanced programming organization.

Not only does Sheiko feature significant variation in volume from session to session, and week to week, but you can see it also features significant variations from block to block! This makes Sheiko the most advanced program we’ve looked at thus far.

As such, Sheiko, the way it is organized, is truly most appropriate for late stage intermediate and advanced athletes. For these populations, Sheiko will work quite well. For novices and early intermediates, it is unnecessarily complex and slow moving in terms of weight increases.

Specificity

Unlike say, in our review of Westside, there isn’t a lot to criticize about Sheiko in terms of specificity. Sheiko actually has you performing the vast majority of your volume through the competition movements. Sheiko actually has you performing the movements with regular frequency: three times per week for the bench, twice a week for the squat, and once a week for the deadlift. Sheiko is actually a program designed explicitly for the purposes of powerlifting. Sheiko is a powerlifting program through and through.

There are a few criticisms to levy however. First and foremost, due to the extremely high volume nature of the program, the average intensity of the work done is low. This is done so that lifters can survive the volumes. The average intensity on Sheiko, for each movement, is generally under 70%. Throughout the numbered programs, you rarely, if ever, go above 90%. In fact, for the bench press, you don’t go above 90% until Week 10. In my opinion, the program could be improved via a reduction in total volume and an increase in average intensity.

Perhaps the biggest specificity issue with Sheiko is that might be a little bit too specific. To discuss why, we need to introduce the concept of diminishing marginal returns. The law of accommodation states that the more frequently you’re exposed to a given stimulus, the lesser the magnitude of the adaptation will be. That is, if you tan for 15 minutes over and over again, you’ll get less and less out of each session. The same sort of effect happens when you only do the competition movements.

To make this clear, we’re going to make up some numbers and use examples. Let’s say the first session you do on the competition squat each week has 100% carryover to improving the squat. If you add a second session, due to accommodation, you might only get 80% carryover. If you add a third competition squat session, perhaps you only get 60% carryover. Now, what if instead of doing competition squats, you added a pause squat day as the third day? Well, the pause squat might provide 75% carryover because it is less specific than competition squats. That said, if you already have two days dedicated to the competition squat, adding a movement with 75% carryover is better than simply adding another competition squat day that will only give 60% carryover. This is training economy. At some point, it becomes disadvantageous to be too specific. You need variations.

Sheiko does include a limited amount of variations, but, in my opinion, it could do better. As with the intensity criticism, this is somewhat of a minor fault. In my opinion, you’d only experience marginal improvements from slightly more variation. Nonetheless, it is worth mentioning.

Overload

Sheiko is a percentage based program. In other words, you start with a known competition one rep max and the entire cycle is designed off of that number. The progression works through basic overload. The lifter handles heavier weights and more volumes over time in order for the cycle to culminate in new PRs in Week 16.

Fatigue Management

Sheiko does a fairly good job of managing fatigue despite the high volume nature of the program. This is primarily accomplished with variation in intensity and volume from session to session, week to week, and block to block. While the lifter is occasionally hit with extremely difficult weeks, these weeks are always followed by lighter, less demanding weeks. The same holds true for the particular blocks.

Likewise, the overall frequency of #29, #30, #31, and #32 limit fatigue to a great extent. While individual session volume is quite high, you’re only training three times per week. Generally speaking, you’re only doing 2-3 exercises for the lower body and upper body each workout. For most, this is manageable.

However, in my opinion, Sheiko does feature needlessly high volume and there are certain demographics who simply won’t be able to recover from the workloads. Just to give you an idea, the easiest Sheiko squatting block is #29. On that program, you do literally twice the overall volume that is present in a month of doing the Texas Method. The Texas Method is known to give older trainees recovery issues. What do you think Sheiko will do?

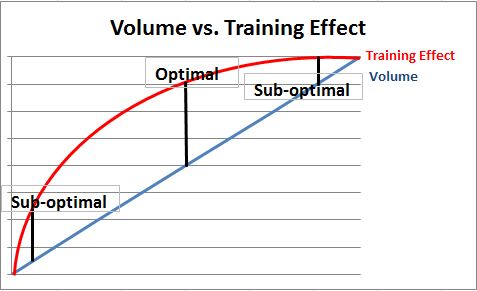

Here’s the thing. An optimal dose-response relationship exists between the amount of volume that you do and the training effect that you get. You’re neither shooting for the minimum necessary volume to progress nor the maximum amount of volume you can recover from. Somewhere in the middle there is a level of volume that produces the greatest training effect relative to the work done.

What you want to shoot for is maximizing the area under the curve. This is going to give you the greatest return on investment for your training time. Now, you might be thinking, why don’t I just go for the highest volume possible to get the maximum gains? I am willing to sacrifice as much time as it takes. That is a commendable attitude, but the problem is that you can only recover from so much. If you push towards that limit too quickly, you short circuit your long term potential.

Think of it like this. What do you have to do to produce further gains when you’re already adapted to high volume? You have to do super high volume. If you turn to super high volume programs too early, you have nowhere to go after that. You’ll pass your peers in the short term, but by the time they work up to the same levels of volume that you’re using, they’ll be stronger because they received more training effect per volume performed as they slowly upped volume over time.

You have to remember that there is a large area of “effectiveness” in-between “not enough volume” and “too much volume”. The question isn’t whether or not you’ll make progress; the question is whether or not you’ll make optimal progress. Like most things in lifting, the moderate path probably contains the answer on this one. There is no need for these high volume programs… until you can’t make gains on anything else.

Individual Differences

The single biggest failing of the numbered Sheiko routines is that they completely ignore individual differences both in terms of load used and overall volume.

If you’re running a strict interpretation of Sheiko, you only increase your maxes at the end of each cycle when you perform at a meet. What if you get stronger ridiculously fast during the training cycle? Sheiko is already a low volume program and this might mean that you’re spending the vast majority of your training time in the low 60%s in terms of intensity. Needless to say, this isn’t optimal.

Even more importantly, there is no volume autoregulation. Everyone needs different amounts of volume! Some days are better than others even for the same individual. A program like Sheiko, which mandates high volumes, is going to just bury a lot of people. The higher stress the program is, and the higher the level of advancement of the athlete who uses the program, the more important it is to account for individual differences. Sheiko ignores individual differences.

Now, to be fair, Sheiko never intended these example programs to be run as gospel, cookie cutter style templates. He personally designs each template for each trainee. In this manner, he can regulate, but not autoregulate, the total volume and load. If he is there in person to coach them, he can personally monitor and make changes to the workload on a daily basis. For those without direct access to Sheiko though, you’re basically just ignoring individual differences on this program.

Regardless, overall, Sheiko numbered programs run as cookie cutter templates do not rate well at all on individual differences.

Overall

Sheiko is one of the best cookie cutter programs that a powerlifter can run. Of all the copy/paste programs we’ve looked at thus far, Sheiko is easily the best… but it is still sub-optimal. Cookie cutter programs can never produce top results. They can produce excellent results, but there will always be room for improvement through individualization and autoregulation.

If you’re a late stage intermediate trainee, or an advanced trainee, Sheiko is not a bad way to go at all. The programs have proven incredibly successful for a variety of top raw powerlifters across the globe. You can always move on to the MSIC programs or contact Sheiko for personal coaching when the numbered routines stop working.

This said, Sheiko, in my opinion, is sub-optimal. The volume is too high for some populations, the intensity is a bit too low for my tastes, there’s a slight lack of variation, and, most importantly, there is zero autoregulation. Without autoregulation, I don’t believe a program can be optimal for the late stage intermediate or advanced athlete.

Moving Forward

Next up on our review list is the Smolov routines. We’ll take a look an extended look at the Smolov squat cycle and a shorter glimpse at the Smolov Junior bench cycle. These routines are absolutely brutal. Both their extreme nature and the extreme results they produce has made them incredibly popular among masochistic internet lifters. We’ll take a look at the utility of Smolov for a powerlifter in the next review.

Did You Enjoy The ProgrammingToWin Series?

If so, you’ll absolutely love our eBook ProgrammingToWin! The book contains over 100 pages of content, discusses each scientific principle of programming in-depth, and provides six different full programs for novice and intermediate lifters. Get your copy now!

Like this Article? Subscribe to our Newsletter!

If you liked this articled, and you want instant updates whenever we put out new content, including exclusive subscriber articles and videos, sign up to our Newsletter!

Questions? Comments?

For all business and personal coaching services related inqueries, please contact me:

[contact-form-7 id=”3245″ title=”Contact form 1″]

Table of Contents

Powerlifting Programs I: Scientific Principles of Powerlifting Programming

Powerlifting Programs II: Critical Training Variables

Powerlifting Programs III: Training Organization

Powerlifting Programs IV: Starting Strength

Powerlifting Programs V: StrongLifts 5×5

Powerlifting Programs VI: Jason Blaha’s 5×5 Novice Routine

Powerlifting Programs VII: Jonnie Candito’s Linear Program

Powerlifting Programs VIII: Sheiko’s Novice Routine

Powerlifting Programs IX: GreySkull Linear Progression

Powerlifting Programs X: The PowerliftingToWin Novice Program

Powerlifting Programs XI: Madcow’s 5×5

Powerlifting Programs XII: The Texas Method

Powerlifting Programs XIII: 5/3/1 and Beyond 5/3/1

Powerlifting Programs XIV: The Cube Method

Powerlifting Programs XV: The Juggernaut Method

Powerlifting Programs XVI: Westside Barbell Method

Powerlifting Programs XVII: Sheiko Routines

Powerlifting Programs XVIII: Smolov and Smolov Junior

Powerlifting Programs XIX: Paul Carter’s Base Building

Powerlifting Programs XX: The Lilliebridge Method

Powerlifting Programs XXI: Jonnie Candito’s 6 Week Strength Program

Powerlifting Programs XXII: The Bulgarian Method for Powerlifting

Powerlifting Programs XXIII: Brian Carroll’s 10/20/Life

Powerlifting Programs XXIV: Destroy the Opposition by Jamie Lewis

Powerlifting Programs XXV: The Coan/Philippi Deadlift Routine

Powerlifting Programs XXVI: Korte’s 3×3

Powerlifting Programs XXVII: RTS Generalized Intermediate Program