I’ve mentioned this at the beginning of every article in this series and I’ll continue to do so here: I drew heavily from Starting Strength to create this material. If you enjoy biomechanical analysis, do yourself a favor and pick up a copy of Starting Strength

. There is literally no other book in existence that spends 300+ pages analyzing the powerlifts in the context of physics and mechanics. If you grasp this material, you’ll begin to be able to develop your own ideas about optimal technique.

When this article is finished, a full argument for the optimal powerlifting deadlift technique will have been presented and articulated.

Before we can move forward, we need to take a look at what is already behind us. In Part VI, the mechanics behind proper deadlift setup were covered. In particular, Part VI established that: a) the bar must start directly over the middle of the foot, b) the hips must start relatively high, and c) the shoulders will start slightly in front of the bar. If you already find yourself arguing, and you haven’t read Part VI yet, I encourage you to do so now. The rest of this article hinges upon the foundation already laid down there.

To back track a bit further, the very first article in this technique series, Part I, presented a few of the most important criteria for determining optimal powerlifting technique. Chief among those not already mentioned are the ideas that we should minimize all relevant moment arms on the lifter/barbell system and that we should minimize range of motion whenever possible.

This is article is long and extremely detailed because the argument I’m presenting here is complex and very important. Picking a technique that is not optimal for you might cost you records, championships, and other rewards. Nonetheless, if you’d rather watch than read, the following video contains a highly abbreviated version of the discussion below:

Deadlift Moment Arm Analysis

Are there any moment arms at work in the deadlift? As a matter of fact, there are. A short moment arm may exist between the knees and the bar depending on your technique. However, in all forms of the deadlift, a long moment arm between the hips and the bar can be observed. In nearly all instances, proper deadlift technique, for the purposes of powerlifting, involves minimizing this moment arm.

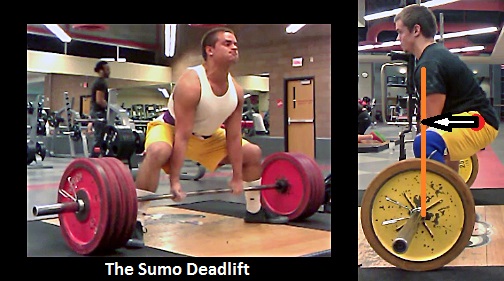

Sumo Deadlifts

The next logical question to ask is if there is any way to shorten this moment arm. And, of course, there is. You may have heard of the one of the more popular techniques used by powerlifters already; we call it the sumo deadlift.

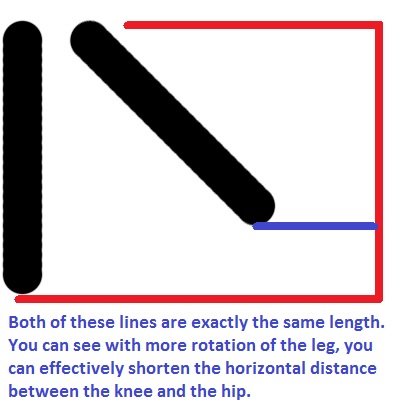

As in the wide stance low bar squat, the wide stance employed by the sumo deadlift shortens the effective length of the thigh by decreasing the horizontal distance between the knee and the hip. This occurs because the wide stance necessitates that the leg is held at an angle and when the leg is held at an angle, it simply displaces less space horizontally. This is easier to see than to describe.

Rounded Deadlifts

There exists one additional way to shorten the moment arm at the hips and it is the more common “trick” used by powerlifters: back rounding. That’s right, rounding your back is probably the single best way to improve your leverage in the starting position of the deadlift. Let’s examine why this is the case.

For one, rounding the back depresses the shoulders which allows the arms to hang lower. This increases the effective length of the arms in starting position.

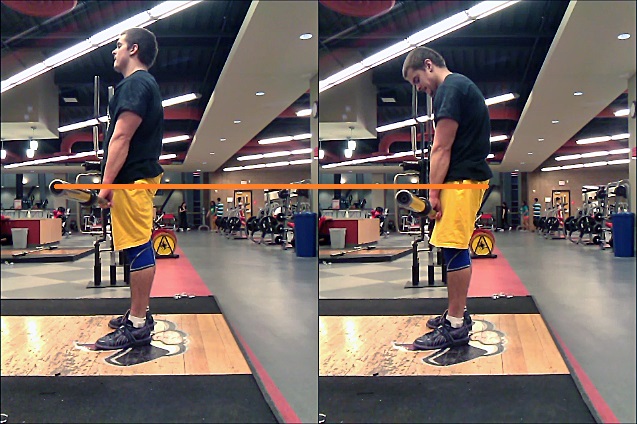

Notice the difference in bar height just from a tiny bit of upperback rounding. Imagine the difference when your back is in full flexion.

Secondly, rounding the back decreases the effective length of your trunk segment. A straight back will displace more space horizontally, as seen from the side, than a round back will. Basically, your spine’s length doesn’t change. The shortest distance between two points is a straight line. So, with a straight back, you can cover more ground because a straight line more efficiently covers a given distance. A round back, and thus a round line, can’t cover as much distance because it isn’t straight. Sorry if that is pedantic, but, again, this is easier to see than to describe.

Notice the shorter distance between the shoulders and hips with the round back. Also notice the shorter distance between the hips and the bar. Lastly, note the more open hip and knee angles when you round your back.

In combination, the above two factors allow for a greater hip height in the deadlift which does three very important and very interrelated things:

1) A greater hip height allows for the hips to be closer to the bar in the starting position. This reduces the moment arm as seen between the hips and the bar. A higher hip height equals better leverage. Better leverage means less muscular force is required to move the same weight.

2) A greater hip height allows for a more open hip angle. All things equal, a more open joint angle can operate more efficiently than a more closed joint angle. Can you quarter squat more than you half squat? Of course you can. A quarter squat puts the knee joint in a more mechanically advantageous position and has a shorter RoM. The same thing happens to your hip joint when you round your back at the beginning of a deadlift.

3) A greater hip height also corresponds to a more open knee angle in the starting position. This is advantageous for exactly the same reason that a more open hip angle is advantageous.

Rounded Pulling Analysis

So, as of now, we’re left with three pulling styles to consider: the flat-back conventional deadlift, the round-back conventional deadlift, and the sumo deadlift. It is only natural to ask, which is best for the purposes of powerlifting? First, let’s tackle rounded vs. flat and then we’ll address conventional vs. sumo style.

On the surface, a rounded back seems to be a huge win for the purposes of powerlifting. The rounded back decreases the one relevant moment arm in the movement and greatly improves our joint angles in the starting position. However, the case is not so clear because round back pulling constitutes a trade off.

When you pull with a rounded back, you must eventually straighten out your spine. The rules of the deadlift mandate that you stand up straight with your shoulders back. This is not possible with a spine that is in flexion. When you pull with a rounded back, the knees and hips can fully extend without you actually finishing the pull. Why? Because your back is still round; you must stand up straight. Simply put, your back, with no help from the hips or knees whatsoever, must finish the top of the pull all by itself.

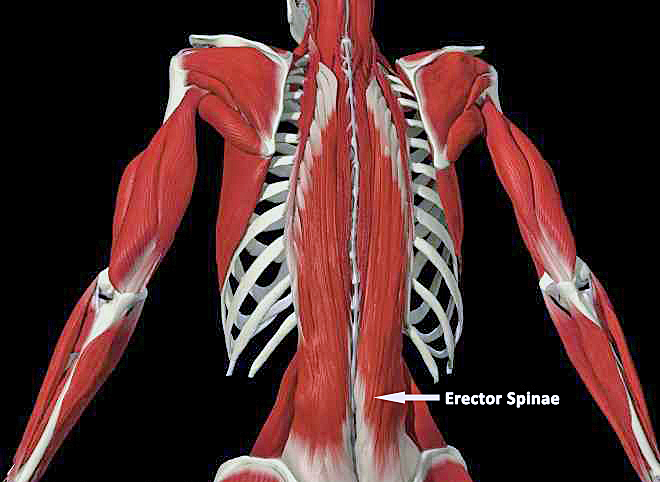

What musculature is responsible for extending a curved spine under a load? The answer is the spinal erectors (erector spinae). This is a group of muscles that runs up and down either side of the spine.

Erector spinae’s natural function is isometric. Simply put, the lower back muscles are actually meant to prevent the back from rounding. They are not designed to extend a flexed spine that is under a load. They are inefficient at doing so.

The conventional deadlift has a reputation for being “strong off the floor” and “harder at lockout”. If you think about this, it doesn’t actually make any sense. Near lockout, the hips are closer to the bar, the knees are more open, and the range of motion is shorter. All signs point to this being the easier part of the lift. And it is. This is why people can rack pull (above the knees) far, far more than they can pull from the ground.

So why do conventional pulls get “hard” at lockout? Because the vast majority of competitive conventional pullers round their back. It is extremely difficult for the lower back to “unround” while it is being pulled down by hundreds of pounds. Again, this is not the job the erector spinae were designed to do; they are not good at this job.

If this is the case, why do most people round their back? The truth is that the hardest part of the deadlift is actually the bottom part of the range of motion. With a conventional deadlift stance, most people don’t have the isometric lower back strength nor do they have the hamstring strength to break the weight from the floor while holding their back flat.

Remember, rounding improves your leverage in the bottom position in nearly every single possible fashion. So, instead of just leaving the bar there stapled to the floor, the body assumes a position of better leverage by rounding the back bit by bit until leverage is improved enough for the bar to start moving.

Much like using a sink and heave technique in the bench, round back pulling is a way to overcome a weak point in the range of motion using technique. Sure, rounding your back screws up your leverages at lockout, but that doesn’t matter if you can’t even break the weight off the floor if you don’t round.

For those who can hold their back flat off of the floor, the lockout will not be the most difficult part of the range of motion even if they are a conventional deadlifter.

Rounded vs. Flat Pulling

This is all well and good, but the most important question here is should we round our backs or not? The reality is that there isn’t much of a choice for most people. For many people of average proportions, and for most with short arms, they’re simply going to be too bent over in the starting position to hold their back completely flat with a maximal weight.

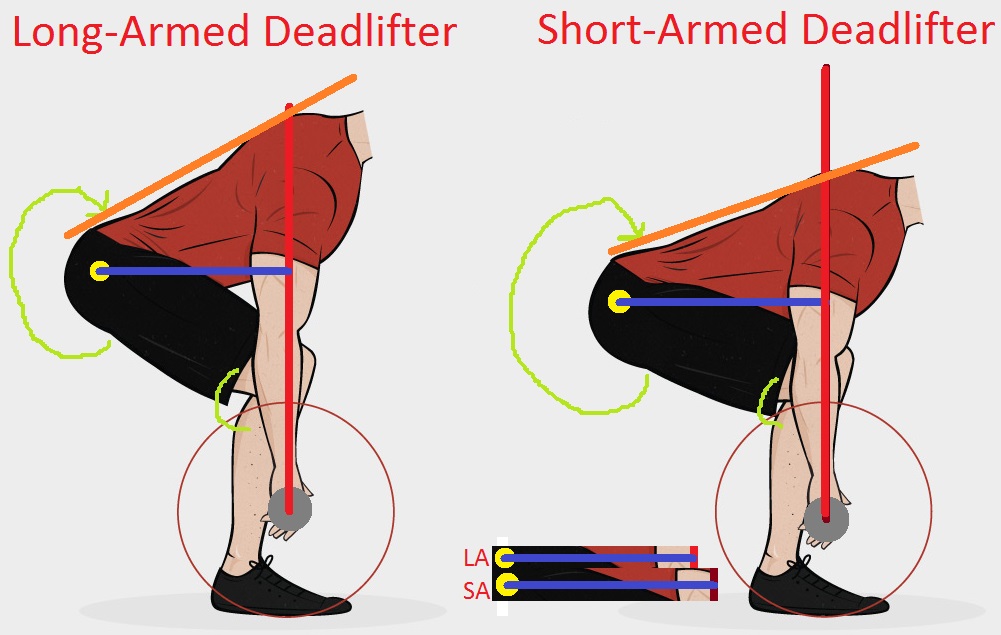

Note the back angle of each lifter marked by the orange line. The shorter your arms, the more horizontal you’ll be in the starting position. Also note how literally every important moment arm or joint angle is worsened by having short arms.

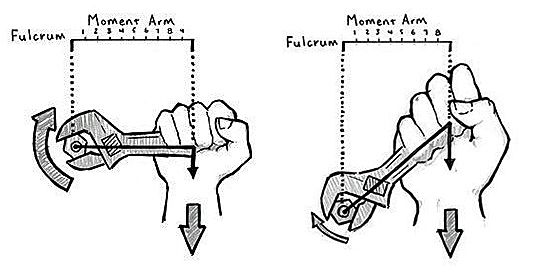

The more bent over you are in the deadlift starting position, the more difficult it is for the lower back to prevent rounding. Why? Well, the more bent over you are, the longer the moment arm between the back and the bar is going to be. As we’ve already learned, the longer a moment arm is, the more leverage you have to overcome.

The longer the moment arm, the stronger the moment arm. Photograph: Mark Rippetoe. Starting Strength: Basic Barbell Training. Rev. 3rd ed. 2012.

If you have a relatively bent over starting position in the conventional deadlift, due to your body type, the limiting factor in your deadlift will probably always be the lower back. As your back fails to hold flat off the floor, you’ll struggle to “unround” at the top.

However, those who have long arms will typically be upright enough in the deadlift starting position that they don’t need to round their backs very much. The more upright back angle means that they simply don’t need as much isometric lower back strength to maintain their position.

Sumo vs. Conventional

Luckily for those who cannot stop their back from rounding on heavy conventional pulls there is a solution. You can pull sumo. Because the sumo stance shortens the thigh segment relative to the trunk, you don’t have to lean over as much to get the scapula directly over the bar. In other words, sumo automatically allows for a more upright back angle that requires far less lower back strength to maintain.

Note how the sumo deadlift has a much more vertical back angle. This position requires less lower back strength to maintain.

However, much like rounded pulling, sumo pulling also represents a tradeoff. That said, the sumo tradeoff is a much more equitable deal.

As we’ve already demonstrated, when you use a sumo stance, you decrease the moment arm between the hips and the bar. In effect, this makes extending the hips much easier. In addition to the shorter range of motion, this is why sumo pulls have a reputation for being easier to lockout.

The sumo stance shortens your range of motion because standing with your legs at an angle decreases the amount of vertical displacement they cause. In other words, when you stand wide, you’re shorter. Try it for yourself and see. Being shorter with the exact same arm and torso length means your range of motion is also shorter. As always, a shorter range of motion helps.

The orange line represents the height of the bar at lockout in the conventional pull. Notice how much lower it is with sumo.

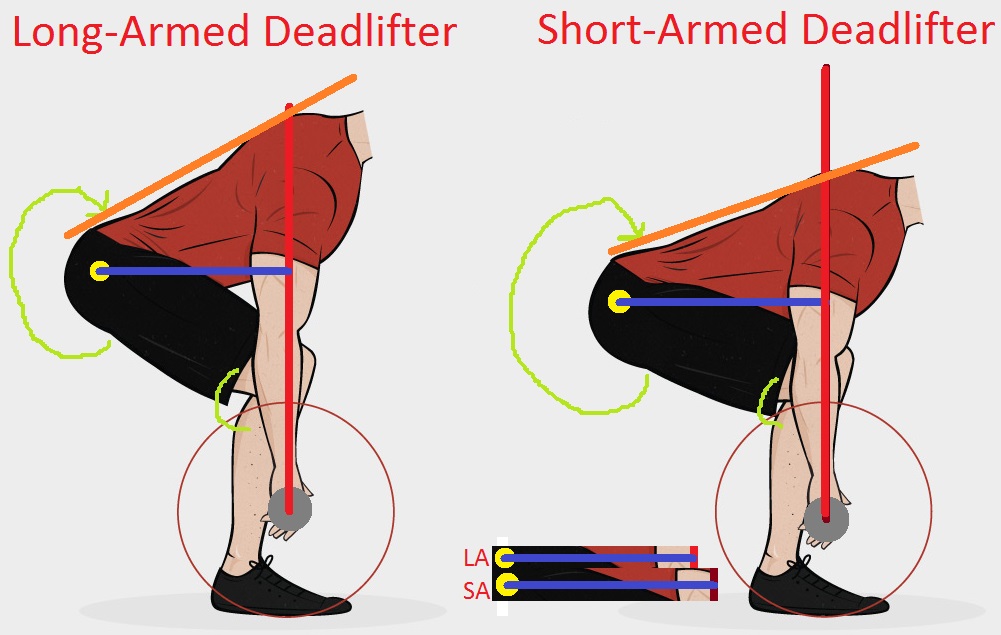

So, if sumo minimizes both the moment arms and the range of motion involved in the movement, AND removes the lower back as the limiting factor in the kinetic chain, why doesn’t everyone just pull sumo? The answer is that, when the legs are shortened relative to the back, the hips must drop lower in order for the scapula to stay directly over the bar. This both closes the knee and hip angle.

Take a closer look at the knee and hip angles with each stance. Notice how much more open the knee angle is in the conventional deadlift?

The more closed hip angle tends to be mitigated by the shorter moment arm between the hips and the bar; however, there is nothing to mitigate the effects of the more closed knee angle. The reality is that the sumo deadlift requires significantly more quadriceps strength than the conventional deadlift.

Therein lays the tradeoff with the sumo deadlift. Yes, you shorten the range of motion; yes, you minimize the relevant moment arms; yes, you remove the lower back as the weakest link in the chain; BUT, you also make the weakest part of the range of motion, right at the bottom, even harder.

Taking a Stance

So… How should we pull? To answer this, we need to take into account the combination of both your anthropometry (body type) and your individual muscular strengths and weaknesses.

The hardest mechanical part of of the deadlift is breaking the bar from the floor. Off the ground, you must break the bar from the floor from a dead stop. Off the ground, the joint angles are in the most closed position that they will be for the entire lift. Off the ground, your leverage, the distance between the hips and the bar, is the worst that it will be at any point in the lift. The bottom line is that getting the bar off the ground is the hardest part of a raw deadlift.

Look at the back, knee, and hip angles of the bar in each position. Near lockout, every single one improves.

While sumo both improves our overall leverage, by reducing the one significant moment arm at the hips, and shortens our range of motion, it just so happens that it also tends to weaken us right at the hardest part of the lift: the bottom. Remember, sumo often removes back strength as the limiting factor. That said, it often just replaces back strength for leg strength as the main limitation.

For those with short arms, this is generally advantageous. People with short arms are usually so bent over in the starting position that they simply do not have the necessary leverages to stay flat on maximal pulls. Their pulls will always be limited by the ability to unround at the top. Rounding makes the lockout inefficient and forces you to rely upon a muscle group (erector spinae) doing a job that it is not even designed to do.

For those with medium arm lengths, things can go either way. Often times, through a lot of diligent training, people of average proportions can be trained to keep their back relatively flat. They usually still round noticeably, but it doesn’t get so bad that their lockout is completely compromised. Likewise, sumo can often be trained to be the more productive style for these individuals as well. Because they don’t have a naturally upright back angle in the conventional pull, it doesn’t take an inordinate amount of specific training for their leg strength to eventually overtake their back strength. For those of medium arm lengths, the style they pull more with depends more so on their individual muscular strengths and weaknesses than their leverages. Realistically, whichever style they train the most will be their strongest style.

For those with long arms, the conventional deadlift is generally going to be stronger than the sumo pull without a lot of specific training. It is important to understand why. Remember, back strength is often the limitation in the conventional pull. However, it takes less strength, less force production, to hold your back in place when it is at a more upright angle.

Imagine the following scenario. We have two lifters with the exact same lower back strength. However, one lifter has longer arms. The lifter with longer arms will be more upright in the starting position. Even though his back is only just as strong as his counterpart, the more upright back angle will reduce moment force on his back muscles thus allowing him to stay flatter with less effort. This is the advantage of minimizing moment arms. Thanks to his body type, this has already been done for him.

Because of their arm length, and thus naturally more upright back angle, longer armed lifters already tend to be more limited by their leg strength than back strength. Switching to sumo, for them, only exacerbates the problem.

The more naturally upright back angle produced by longer arms tends to shift the weak link in the system from being the lower back to being the legs.

But hold on, what tends to happen when leg strength becomes the limiting factor in a deadlift? The back rounds until leverage improves enough for the bar to leave the floor. That’s right; even for long armed lifters, usually the back will end up rounding anyways. The only difference for longer armed lifters is that, instead of the back rounding due to its own weakness, it rounds to offset the weakness of the legs. Because of this fact, longer armed lifters generally have more success “unrounding” at the top. Their back is still their strong point and they usually have enough in the tank to finish the pull. This isn’t always the case, though. Unless they do something to bring up their legs, eventually, back rounding will lead to missed pulls at lockout.

Bringing It All Together

So it would seem like I am parroting the oft-repeated cliche when it comes to deadlift style: sumo works better for short arms and conventional works better for long arms. Without specific training, this does tend to be the case. But what about with specific training? Now the answer isn’t so clear. Let’s recap what we know.

Regardless of anthropometry (body type), you will always be able to lockout more weight with sumo if you can get it to break the floor. This is primarily due to two things: a) sumo affords you the ability to keep your back flat quite easily due to the very upright back angle, and b) sumo both reduces the range of motion and brings the bar closer to the hips both of which make the lockout far easier. In the end, sumo is always limited by leg strength and the ability to break the bar from the floor.

Regardless of anthropometry (body type), you will always be able to break more weight from the floor with a rounded back conventional deadlift. This is primarily due to two things: a) the rounded back depresses the shoulders and increases the effective length of the arms in the starting position, b) the longer arms, in combination with the shorter, rounded back, open up the knee and hip angle in the starting position thus improving your starting leverages. This said, in the end, regardless of body type, the conventional deadlift is almost always going to be limited by your ability to unround at the top of the pull. And your ability to unround at the top is always going to be limited by lower back strength.

The rounded back puts the legs in a much more favorable position while placing the lower back in a much worse one. Notice how sumo does the exact opposite.

In the end, there is no way around it: each deadlift style is limited specifically by individual muscular strengths and weaknesses. Certain body types influence the relationship one way or the other, but the relationship remains the same. Sumo is limited by the legs and Conventional is limited by the back.

My Recommendation

It is my opinion that you will be strongest with the style of deadlift that is suited best to your muscular strengths and weaknesses and not necessarily the style that is best suited to your body type. Again, your body type isn’t irrelevant; body type influences how easy it is, in the context of a heavy deadlift, for the back to be stronger than the legs or visa versa. Ultimately though, it comes down to your muscles and not your bones.

Because of this, my personal recommendation is to use the sumo deadlift. In the end, the “leverages”, as defined by the moment arm length between the hip and the bar, are still better with sumo. The range of motion is still shorter. And if it just comes down to which muscles are stronger, why not pick the style where our strength will go the furthest?

I’d rather be limited by my legs than my back for training purposes as well. Nearly everyone in powerlifting agrees that there is a unique phenomenon that occurs with regards to training heavy conventional deadlifts: localized lower back fatigue. The “lower back” is a relatively small group of muscles compared to the legs. When smaller muscle groups are exposed to huge loads, they experience huge fatigue. As a result, many powerlifters resort to pulling once every 7-10 days. Some only pull once every other week. Further still, some guys don’t even deadlift at all until they’re at the meet.

Frankly, training a lift that infrequently is not conducive to optimal progress. Shifting the fatigue load over to the legs allows for more frequency and higher volumes than you can use with the conventional deadlift. Not only can you use more frequency and more volume, but the legs are much easier to grow and strengthen than the lower back. The bigger a muscle group is, the more potential it has for mass increase and strength gains.

If you train with a deadlift bar, sumo is even more advantageous. Because deadlift bars bend and flex before they leave the ground, they help out at the bottom of the range of motion while not giving any specific help at at the top. After all, you’re still locking out in exactly the same place. You’re just starting off from a higher position. This higher starting position negates some of the disadvantages of the sumo style. When you have a higher starting position, the knees and hips can assume more open joint angles. Thus, if you pull with a deadlift bar, you’ll get more “carryover” from using the bar if you pull sumo.

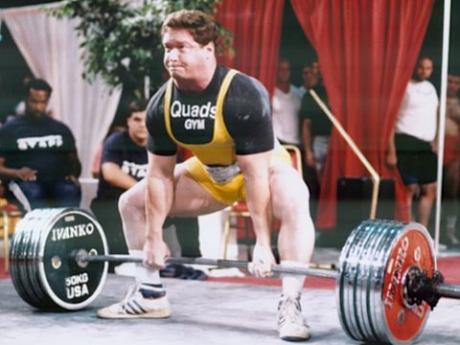

Belyaev (top) is using a deadlift bar. Tuchscherer (bottom) is using a stiff bar. Note the difference in bar bend.

Lastly, grip is less of a factor in the sumo deadlift. If you have small hands, this may be an important consideration. For conventional deadlifters, the range of motion is longer, but, generally, so is the time under tension. People who round their backs, even slightly, tend to “grind” out their heavy conventional pulls. Grinding out a rep takes time. Taking that time gives your grip a chance to fail.

If you pull sumo, you either break the bar from the floor or you don’t. Generally, when the bar breaks the floor, it flies right up to lockout. Because breaking the bar from the floor is nearly universally the sticking point in sumo deadlifts, once you pass the sticking point, it is smooth sailing. This reduced time under tension gives less opportunity for the grip to fail. Grip limitations are frustrating and can take quite a bit off of your total. Sumo helps minimize this particular challenge.

To be succinct, I personally recommend the sumo deadlift over the conventional deadlift. The only exception is if you’ve already been training for years and years using the conventional style. It is likely that you’d need also need years for the sumo pull to catch up and surpass your conventional deadlift. For those who are already highly competitive, you might not be able to afford spending years totaling less than you otherwise would had you just stuck to conventional.

Deadlift World Records

I’m sure many of you think I’ve gone off the deep end here. Sumo deadlift… for (nearly) everybody? Sure, why not? If optimal deadlift style depends on individual muscular strengths and weaknesses (and technique which we’ll cover in the next article), why not pick the style that has the better leverage and is easier to train more often and with higher volumes? Why not?

If you think that this recommendation is unprecedented in powerlifting, you’re incorrect. Take a look at the raw world record list:

World Records:

634@123, Conventional

628@132, Conventional

694@148, Sumo

716@165, Sumo

791@181, Sumo

861@198, Sumo

901@220, Sumo

890@242, Sumo

881@275, Conventional

939@308, Conventional

1015@SHW, Conventional

You’ll notice that nearly all of the lighter weight classes feature records set by sumo pullers. In fact, the 242 record is actually higher than the 275 record (we’ll talk in the next article about why most big guys don’t pull sumo). Next, I’m going to show a highlight video of all the raw sumo world records. I want you to pay attention to arm length:

http://youtu.be/jyHy5lrsJh0

All of these guys have long arms (besides Belyaev). They still use the sumo deadlift. And they’re world record holders to boot. You can see that even for people with long arms the sumo deadlift still often ends up being the most productive stance for powerlifting.

Moving Forward

So, what have we learned? While there definitely exists a relationship between anthropometry and preferred pulling style, ultimately, you can find examples on both sides of the coin, long-armed-sumo, and short-armed-conventional, that seem to defy the stereotype. Why? Because optimal pulling style comes down to individual muscular strength and weaknesses. Body type is the secondary factor. If you have a super strong lower back, you’ll pull more conventional. If you have super strong legs, you’ll pull more sumo.

Ultimately, I recommend pulling sumo. The overall “leverage” is better for everyone, the range of motion is shorter, and it is easier to grow and strengthen the legs than it is to grow and strengthen the lower back. With sumo, you can pull for more volume and pull more often. In the end, I believe this leads to a stronger training effect. Check the world records. They seem to verify this exact sentiment.

Again, I have to stress, if you enjoy this type of biomechanical analysis, you really need to do yourself a favor and pick up Starting Strength. All of the principles and tools I’ve used here can be distilled from reading that text. Trust me, the book isn’t just about the program; it is about physics and biomechanics as well.

In Part VII, we’ll cover sumo deadlift technique. Unlike the conventional deadlift, which you can mostly “grip-and-rip” with good success, the sumo deadlift requires a significant amount of flexibility and technical skill. If you don’t perform the movement correctly, you get none of the advantages of the stance and you keep all the disadvantages. Technique is paramount to being a good sumo puller.

Whether you pull sumo or conventional, stay tuned for Part VII. Technique tips, tricks, and advice will be given that is pertinent to both styles.

Like this Article? Subscribe to our Newsletter!

If you liked this articled, and you want instant updates whenever we put out new content, including exclusive subscriber articles and videos, sign up to our Newsletter!

Questions? Comments?

For all business and personal coaching services related inqueries, please contact me:

[contact-form-7 id=”3245″ title=”Contact form 1″]

Table of Contents

Part I: The Scientific Principles of Powerlifting Technique

Part II: Squat Form Analysis

Part III: How to Squat Like A Powerlifter

Part IV: Bench Form Analysis

Part V: How to Bench Press Like A Powerlifter

Part VI: Deadlift Setup Science

Part VII: Deadlift Form Analysis

Part VIII: How to Deadlift Like a Powerlifter

Great article, I can see a lot of time and thought went into this.

Thanks mate.

Thanks Neil!

Do you have any thoughts as to advantages for training the conventional deadlift for competitive sumo pullers? Would you program some conventional training? If so, how?

Steve, I don’t really think I can answer your questions but I will try. Sure, there could potentially be benefits. It would depend on the particular force curve of the individual in question. Sumo style doesn’t completely eliminate the need for a strong back. If a sumo puller thought they needed to bring up their lower back for whatever reason, conventional would be a great movement to use. Because of the nature of the movement, and how heavy it is, and how specific it is, you’d have to use it as a secondary exercise. So, how’d you fit it in would depend entirely on the structure of your program. If you pull once a week, it could be your primary assistance movement for the day. If you pull twice a week, it may even be worth using it as the main movement on your secondary day if you really felt that it would produce a lot of carryover. I don’t think that you necessarily need to use both styles, though. It would completely depend on carryover which would depend, as I said, on the individual’s force curve on their sumo pulls.

Wow wow wow wow and another wow!

Your articles are sooooo damn great. I read a lot about the different lifts and no one is getting in the lifts so detailed as you do!

Especially the pictures/illustrations help out a lot.

I for myself, was always confused about how long/short my leverages actually are. Even though I measured everything and used charts to determine the “right” pulling style, it didn’t really made things clear to me.

What I want to say is that your articles give a great insight!

Please keep on!

Thanks, I appreciate it! Let me know if you need any help with anything.