In all the time I’ve spent on the internet reading and talking about powerlifting, the one question I see asked more than any other is: “Is my program “good”?

Now, “my” program can be substituted for 5/3/1, Starting Strength, The Cube, Westside, Billy Bob’s 5×5, Ronnie Coleman’s 16 Week Bicep Blaster Routine, or virtually any other program that you can think of. Rather than repetitively giving the same answers over and over again, I’ve decided to write a programming series that endeavors to arm readers with all the necessary tools to make those evaluations themselves.

In fact, if you’re interested in educating yourself on this very subject, I highly recommend that you grab a copy of ProgrammingToWin. I recommend it both because it is accurate and thorough and because I know even the average novice can understand the writing and concepts. If you find yourself enjoying these theoretical programming discussions, don’t miss out on a chance to grab a copy of the book for only 9.99.

Once we’ve established the foundational scientific principles of powerlifting programming, I will analyze a variety of the most popular programs one by one. In each breakdown, I will cover the strong and weak points of the program as well as whether or not I’d actually recommend the program for the purposes of powerlifting.

If you’d rather watch than read:

Good, Better, Best

The very first thing that we need to do is move past the false dichotomy that a program is either “good” or “bad”.

In fact, whether or not most programs work is completely dependent on YOU and not on the program. The best program in the world cannot instill the necessary work ethic, consistency, and drive that are required to obtain excellent results in the incredibly demanding sport of powerlifting. The best athletes get the best results often IN SPITE of the training modalities they employ and NOT because of them. Think about that.

I’m willing to bet a lot of money that Michael Jordan would’ve kicked everyone’s ass even if he was running the Herp-a-Derp program.

Back to the point, if you take an untrained, couch potato novice, you can increase their squat max by having them ride a bike or play basketball. You could also take this novice to gym and get them to squat heavy sets of three to five reps. Both methodologies are going to increase their squat max. However, one approach is very clearly “better” than the other.

Good, Better, Best

And that’s the thing when we’re evaluating powerlifting programs; we’re actually trying to evaluate between “good”, “better”, and “best” (and yes, sometimes “bad” too). As an intermediate trainee, you might make good gains on Jim Wendler’s 5/3/1, but would they be as good as the gains you could make on a Boris Sheiko template? Answering questions like this one is going to be the main priority of the powerlifting program article series.

Of course, the next logical question is, “How exactly do we differentiate between “good”, “better”, and “best”? Well, for one, we must establish what the actual objective of a powerlifting program is: improve competition results. Let me just reiterate that. The SOLE purpose of a powerlifting program is to improve your competition results.

The purpose of a powerlifting program is not to get shredded; the purpose of a powerlifting program is not to build muscle; the purpose of a powerlifting program is not to get faster; the purpose of a powerlifting program is not to become “aesthetic”; the program may accomplish these things peripherally, but the main purpose of a powerlifting program is to lift more weight in powerlifting competitions.

As such, the primary consideration in evaluating any powerlifting program is whether or not it will improve your total. It is really that simple.

The General Adaptation Syndrome

Before we can begin laying down the scientific principles of powerlifting programming that will allow us to begin making distinctions between what is “good”, “better”, and “best”, we need to discuss the process by which training actually works.

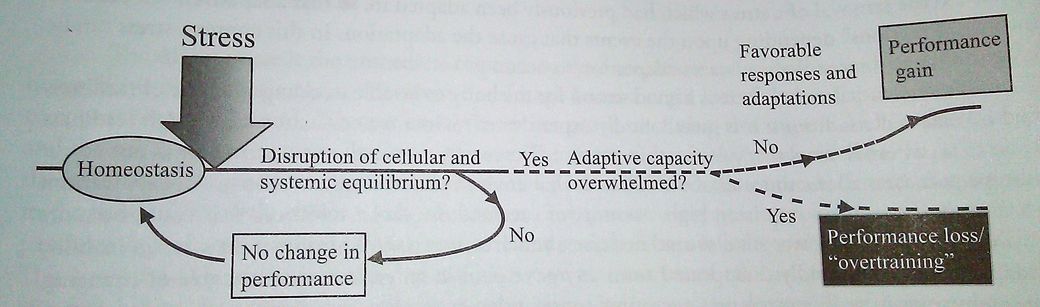

Most of the currently popular theories about why training works revolve around Hans Seyle’s theory of the General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS). According to the GAS, training works because of the process known as the stress-recovery-adaptation response.

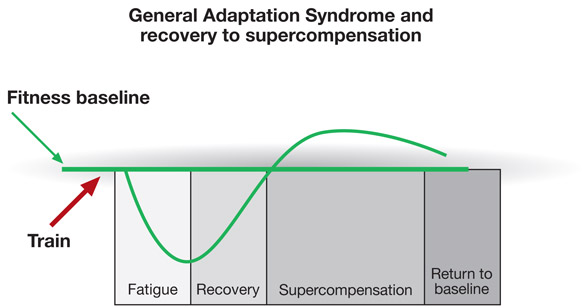

In essence, an outside “stress” is applied in a given dose to the body. Now, these stresses are toxic and, in high enough doses, potentially lethal. Consider a sun tan. When unadapted, pale skin is exposed to sun light, it actually accrues damage (“stress”). Once removed from the stress, the body not only repairs this damage (“recovery”), but the physiological structure is actually improved to prevent further damage from a similar stressor (“adaptation”). GAS is nothing more than one of our primary evolutionary advantages at work.

In terms of training, the dots are easy to connect. Going to the gym and lifting heavy weights causes microtears in muscle fibers, elicits various hormonal responses, and sets off a variety of other metabolic signals that all communicate to the body that “stress” has occurred and the resulting damage now needs to be repaired. Through eating, sleeping, and taking time off from the gym, we can “recover” from this “stress”. Our reward for completing this entire process is further “adaptation”; we get stronger.

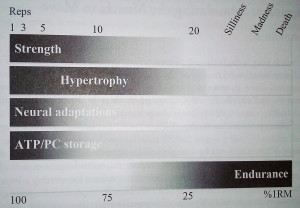

Principle #1: Specificity

Now, it is critical to keep in mind that the GAS only works in our favor for powerlifting if we actually train like a powerlifter. If you’re engaging in a routine that doesn’t call for frequent squatting, benching, and deadlifting, the program might not be specific enough to maximize adaptation. Likewise, if you’re not lifting heavy very frequently, your training may not be specific enough to maximize adaptation.

To maximize powerlifting specificity, we need to keep the reps down. Photograph: Practical Programming 3rd Edition, Mark Rippetoe, Aasgaard Co. 2014.

Specificity in training is a topic unto itself and full coverage of this principle is beyond the scope of this article. However, it is absolutely imperative that you realize that, if you want to be a better powerlifter, you should train on a program that is explicitly designed to increase powerlifting performance. Yes, you should actually use a powerlifting program and NOT a “strength” program. They are two different things.

The body adapts only to the stresses it is exposed to. If you expose your body to high reps, to lots of cardio, to lots of machine work instead of squatting, benching, and deadlifting, you shouldn’t expect optimal results for powerlifting.

Principle #1 is that your training should be specific to the sport of powerlifting.

Principle #2: Overload

The GAS can only continue to work in our favor if we continue to expose our body to adequate doses of stress. Once the body has adapted to a given dose, you’ll experience diminishing returns from continually applying that same dose. For example, we’ve all seen the guy who comes in and benches the exact same weights for the exact same reps every single week. Not coincidentally, beyond a certain point, this guy never gets any stronger.

Remember, the entire point of the GAS is to prevent the body from undergoing damage from a similar “stressor” the next time it is exposed. At a certain point, your body is going to be fully adapted to using a certain amount of weight, a certain amount of reps, or a certain amount of sets. Eventually, you have to go beyond what you’ve done before; you have to “overload” your body.

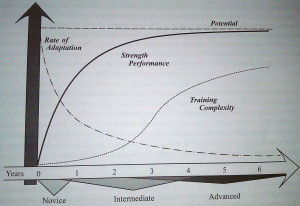

For continued progress in powerlifting, throughout your entire training career, you will constantly have to lift more weight and do more overall sets and reps in order to provide the body with a dose of stress that is high enough to elicit the stress-recovery-adaptation response. The more adapted you become, the bigger that dose has to be. If you’d like more information on this whole process, I highly recommend grabbing a copy of Practical Programming for Strength Training.

Principle #2 is that you must present your body with an “overload” from what you’ve stressed it with in the past; over time, you must lift more weight and/or complete more sets and reps.

Principle #3: Fatigue Management

As in anything, in powerlifting you either “use it” or you “lose it”. If you cease to train, you’ll begin to slowly lose your hard won adaptations. If you don’t practice a certain lift, your skill will deteriorate in that lift.

This fact becomes highly important when considering overall fatigue management. The larger the dose of stress relative to the athlete’s recovery capacity, the longer the recovery process takes. If you mismanage your deadlift workload for example, you may take so long to recover between bouts of stress that you actually begin to detrain while waiting for your next pulling session. Stress must be accumulated properly in order to maximize recovery and prevent any unnecessary detraining.

In other words, timing is critical. Once you’ve completed that stress-adaptation-recovery response, you want to hit your body with the next dose of stress before it has time to start going backwards again. Likewise, you need to ensure that your programming isn’t overwhelming the stress-adaptation-recovery response and not allowing for adaptation to occur at all. Don’t be fooled by extremists: both undertraining and overtraining are very real.

The more advanced you become as a trainee, the more complex your fatigue management has to become as well. Photograph: Practical Programming 3rd Edition, Mark Rippetoe, Aasgaard Co. 2014.

Fatigue management, Principle #3, is the crux of programming: timing your stress doses and recovery periods in such a way that you maximize adaptation over the life of a training cycle.

Principle #4: Individual Differences

One of the single most ignored aspects of powerlifting programming is the law of individual differences. The law of individual differences simply states that, due to a countless myriad of factors, every individual will respond to a given training stimulus slightly differently. Now, this doesn’t mean that benching is going to turn one guy into Arnold and another guy into a string bean; it just means that the precise level of stress, the exact adaptations, and the imposed recovery demands, among other things, are going to differ from individual to individual. Your gains won’t be my gains.

No, we’re not THIS different, but you still won’t get the same results as me even if we do the same thing. Photograph: TheHealthyHomeEconomist.com

Everybody needs a slightly different amount of volume to progress. Everybody can handle slightly different overall workloads. Everybody has slightly different biomechanics which play a part in movement selection. Frankly, I’m very adamant about the fact that training is not optimal if it is not individualized.

Now, most popular programs ignore this fact because most popular programs are written for the masses. These “Pop” programs are designed to be used as cookie cutter templates that you can mindlessly follow. If they were properly individualized to each trainee, they probably couldn’t be easily mass marketed. You wouldn’t have a program; you would have a system.

I hate to be cynical, but sometimes people do what they have to do to sell their products.

Don’t get me wrong: cookie cutter programs often work really well. However, as I said above, they are usually sub-optimal because they tend to ignore Principle #4 – the law of individual differences.

Summary

To recap, as we begin to evaluate some of these popular programs, I want you to keep in mind the idea of “good, better, best”. Only a fool would say that a program “doesn’t work”. We’re not necessarily interested in whether programs work, we’re interested in whether they work optimally.

The entire basis of our evaluation is founded upon an understanding of Seyle’s General Adaptation Syndrome. That is, training works by a process of stress -> recovery -> adaptation. We introduce the stress, we recover, and we come back stronger again and again.

In analyzing some of these programs, we’ll be making extensive use of four principles that are present in any great powerlifting program:

-

- Specificity

You have to actually train for powerlifting. Your training must include lots of heavy squats, benches, and deadlifts.

-

- Overload

If you’re not constantly progressing the weights, reps, sets, and overall volume that you do, you will stop stressing the body. When the body isn’t stressed, it doesn’t adapt. You must do more than you’ve done before.

-

- Fatigue Management

The training cycle must be timed properly. We want to create a synergistic effect between our doses of stress and our recovery periods. If we wait too long between sessions, we’ll begin to detrain. If we don’t wait long enough, we’ll begin to overtrain.

-

- Individual Differences

Everybody is different. Everybody needs a slightly different level of stimulus to force the body to adapt and everyone adapts to those stimuli in slightly different ways. If the training program is not individualized for you personally, it isn’t optimal because it doesn’t take into account individual differences.

If you want more information on the physiology behind adaptation, I’m going to recommend Practical Programming as a great read for you. You can check out my full review of the book here.

Moving Forward

In the next installment of the Powerlifting Programs series, I am going to be discussing training variables: volume, intensity, frequency, movement selection, and more. Without contextual understanding of these facets of training, it isn’t possible to discuss “optimal” programming. After that, we’ll begin our analysis of popular programs one by one!

Did You Enjoy The Powerlifting Programming Series? If so, you’ll absolutely love our eBook ProgrammingToWin! The book contains over 100 pages of content, discusses each scientific principle of programming in-depth, and provides six different full programs for novice and intermediate lifters. Get your copy now!

Like this Article? Subscribe to our Newsletter!

If you liked this articled, and you want instant updates whenever we put out new content, including exclusive subscriber articles and videos, sign up to our Newsletter!

Questions? Comments?

For all business and personal coaching services related inqueries, please contact me:

[contact-form-7 id=”3245″ title=”Contact form 1″]

Table of Contents

Powerlifting Programs I: Scientific Principles of Powerlifting Programming

Powerlifting Programs II: Critical Training Variables

Powerlifting Programs III: Training Organization

Powerlifting Programs IV: Starting Strength

Powerlifting Programs V: StrongLifts 5×5

Powerlifting Programs VI: Jason Blaha’s 5×5 Novice Routine

Powerlifting Programs VII: Jonnie Candito’s Linear Program

Powerlifting Programs VIII: Sheiko’s Novice Routine

Powerlifting Programs IX: GreySkull Linear Progression

Powerlifting Programs X: The PowerliftingToWin Novice Program

Powerlifting Programs XI: Madcow’s 5×5

Powerlifting Programs XII: The Texas Method

Powerlifting Programs XIII: 5/3/1 and Beyond 5/3/1

Powerlifting Programs XIV: The Cube Method

Powerlifting Programs XV: The Juggernaut Method

Powerlifting Programs XVI: Westside Barbell Method

Powerlifting Programs XVII: Sheiko Routines

Powerlifting Programs XVIII: Smolov and Smolov Junior

Powerlifting Programs XIX: Paul Carter’s Base Building

Powerlifting Programs XX: The Lilliebridge Method

Powerlifting Programs XXI: Jonnie Candito’s 6 Week Strength Program

Powerlifting Programs XXII: The Bulgarian Method for Powerlifting

Powerlifting Programs XXIII: Brian Carroll’s 10/20/Life

Powerlifting Programs XXIV: Destroy the Opposition by Jamie Lewis

Powerlifting Programs XXV: The Coan/Philippi Deadlift Routine

Powerlifting Programs XXVI: Korte’s 3×3

Powerlifting Programs XXVII: RTS Generalized Intermediate Program